The people behind the telescope: How CLASSE expertise is supporting science at the edge of the universe

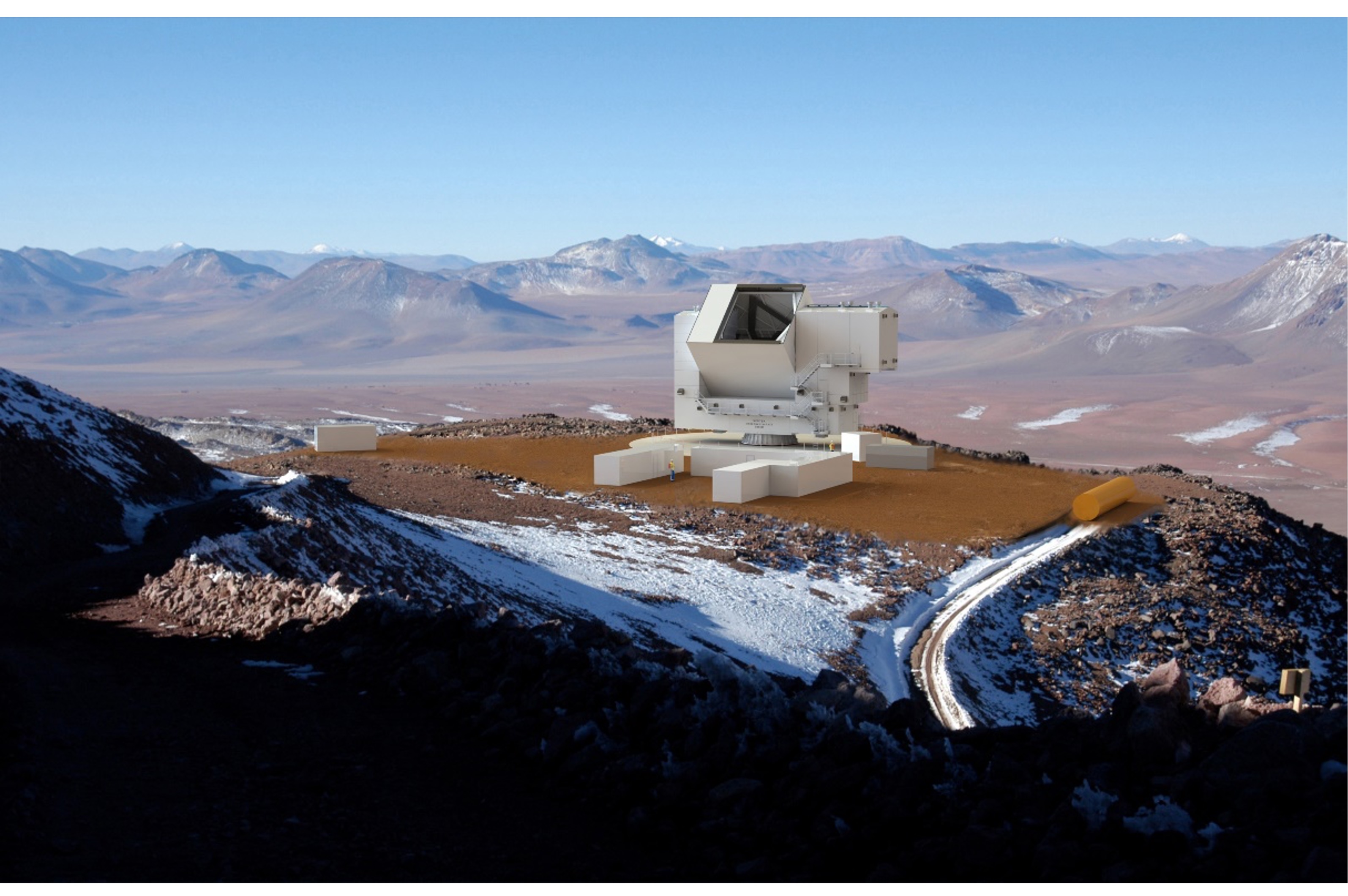

As the Fred Young Submillimeter Telescope (FYST) prepares for first light in 2026, its journey to the high Atacama Desert of Chile’s Parque Astronómico Atacama, has been shaped not only by scientists and astronomers, but by a network of engineers, machinists, electronics specialists, riggers and support staff at the Cornell Laboratory for Accelerator-based Sciences and Education, CLASSE.

The telescope will operate at 18,400 feet above sea level, above much of Earth’s atmosphere, enabling a wide range of ambitious science goals. These include mapping the universe’s evolution from the birth of the first stars and galaxies, measuring the growth of galaxy clusters shaped by dark matter, probing magnetic fields in the Milky Way, and searching for subtle polarization signals in the cosmic microwave background that may point to primordial gravitational waves.

“It is the highest optical-throughput submillimeter telescope ever built, by about a factor of ten,” said Mike Niemack, professor of physics and astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences and lead scientist for FYST’s Prime-Cam instrument. “That opens up a wide range of exciting science, from the cosmic microwave background to new ways of mapping how galaxies formed and evolved.”

Achieving those goals, however, requires meeting some of the most demanding engineering, fabrication and coordination challenges in modern astronomy.

Extreme Requirements, Specialized Skills

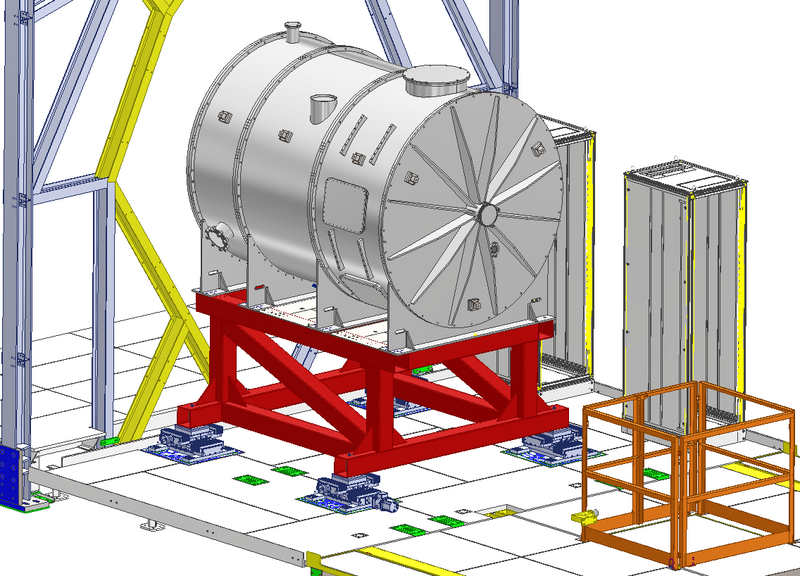

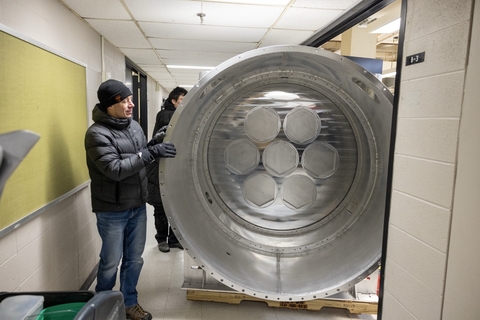

Prime-Cam is one of two instruments planned for FYST. The instrument is being outfitted in the Space Sciences building of Cornell, with multiple low-temperature stages, silicon lenses, optical filters, detector arrays, and readout components. It must operate at cryogenic temperatures, with key detector stages cooled to near absolute zero. It must also maintain precise optical alignment while surviving transport across continents and final assembly at high altitude, where oxygen is scarce and working time is tightly regulated.

Those realities mean the design process does not end when fabrication begins. CLASSE’s ability to adapt designs, respond to testing results and coordinate across technical disciplines plays a central role in supporting a project of this scale.

“There are many areas where CLASSE expertise is critical, including machining, engineering, riggers, procurement, electronics, scheduling, and human resources for helping manage all the people involved in these efforts.” Niemack said. “In other words, many CLASSE team members are playing essential roles in enabling this research.”

Engineering Under Pressure

“With a large and complicated system such as Prime-Cam, there are bound to be redesigns that come up during testing,” said Dave Burke, a mechanical engineer at CLASSE who has supported the project through critical testing and preparation phases.

After an early cool-down of the instrument, where the components are brought to real life operating conditions, Burke and the team identified a performance issue. Excess heat load on the coldest stage of the system was limiting how low the temperature could reach.

“The main requirements of the cryostat include low vacuum, optical alignment, and an instrument temperature of less than one Kelvin,” Burke said. “After the first cool-down, improvements were needed to reduce the power loading on the 100 millikelvin stage.”

That is roughly -457 degrees Fahrenheit.

The team focused on three areas: improving wire management, sealing light leaks and adding a radiation shield to the four-Kelvin plate of the dilution refrigerator. Working against the calendar, the group designed, fabricated and installed the new shield in just one week, immediately before Thanksgiving.

“That hard work bought the team a week of cooling time,” Burke said. “When we came back, we were excited to see the results collected from the latest cool-down.”

The improvements reduced the heat load from 330 microwatts to 30 microwatts and lowered the temperature from 130 millikelvin to 50 millikelvin.

“That was a massive milestone,” Burke said.

Burke also explained that the engineering design for FYST also means designing for people working in extreme environments, particularly the high altitude of the final location.

“At that altitude, the atmosphere is roughly half as dense as that of Ithaca, New York,” Burke said. “Turning a wrench, walking up a ladder, carrying equipment, those tasks become much more difficult.”

Chilean regulations limit work at the site to eight hours per day, making efficiency critical. Burke explained that he and the team accounted for these constraints by designing components that are easier to lift, align and assemble, along with custom tooling to support installation.

“Time is critical,” Burke said. “You have to assume every task will take longer and design accordingly.”

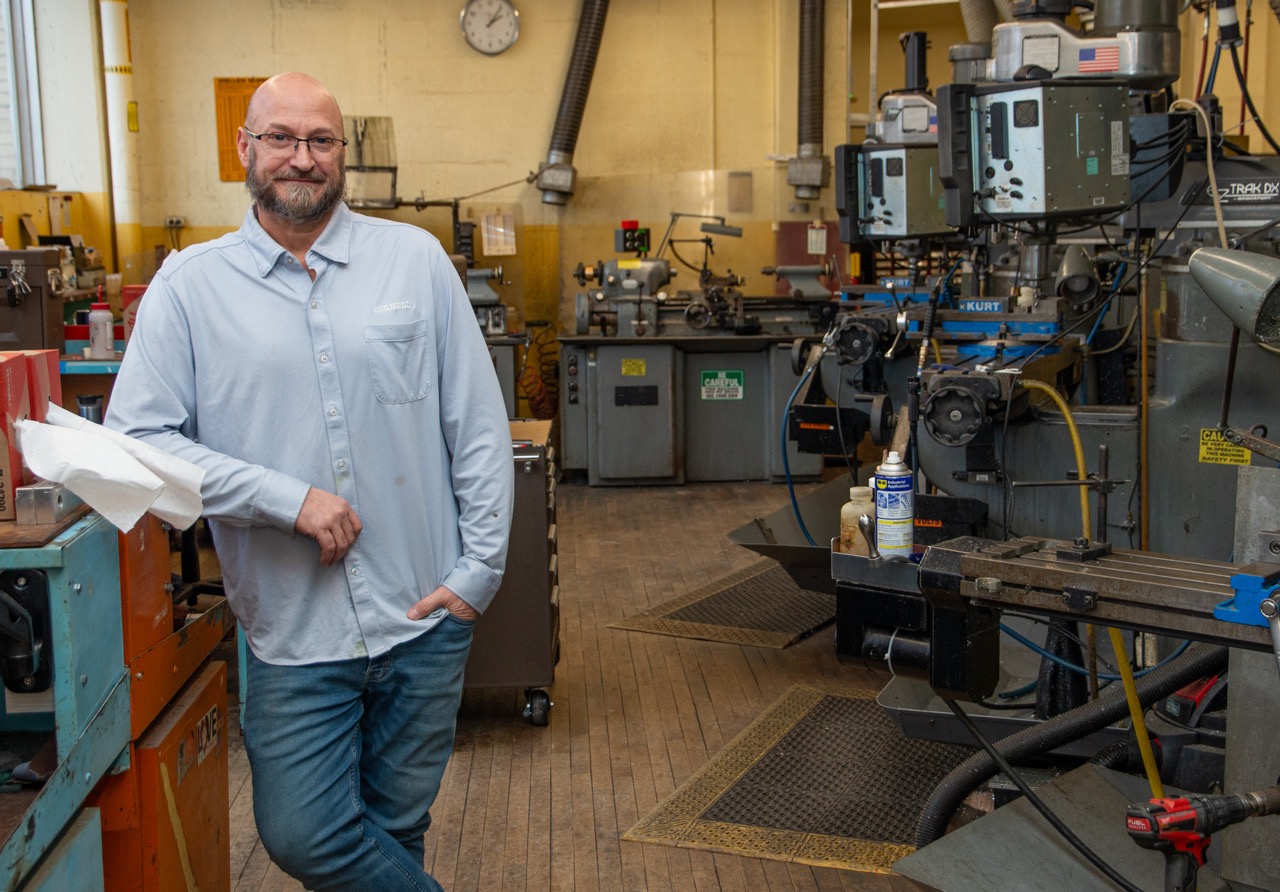

Precision at Scale: The Machine Shop

One of the most substantial components physically supporting the Prime-Cam instrument is the ‘raft’, a one-ton steel structure that carries the large aluminum cryogenic chamber. The Prime-Cam instrument measures six feet in diameter, with numerous interfaces that must align precisely once assembled.

Fabricating hardware of that size required close coordination between Burke and other CLASSE engineers and machinists across both the CLASSE and LASSP machine shops.

“The size and magnitude of this project were challenging,” said Terry Neiss, CLASSE machine shop supervisor. “It required multiple machine shops and some assembly in the lab. The raft itself is carbon steel and extremely heavy. The chambers mounted to it are aluminum and very large, with a vast number of parts working together.”

Although FYST’s extreme operating conditions are addressed in engineering models, machining still had to meet tight specifications. Components built at room temperature must perform reliably after cooling to cryogenic temperatures and withstand transport between continents before final installation.

“We build to the specifications that are given to us,” Neiss said. “Each project contributes to the next. From one project to another, we gain experience with different processes, materials, tooling and tolerances. That experience is vital.”

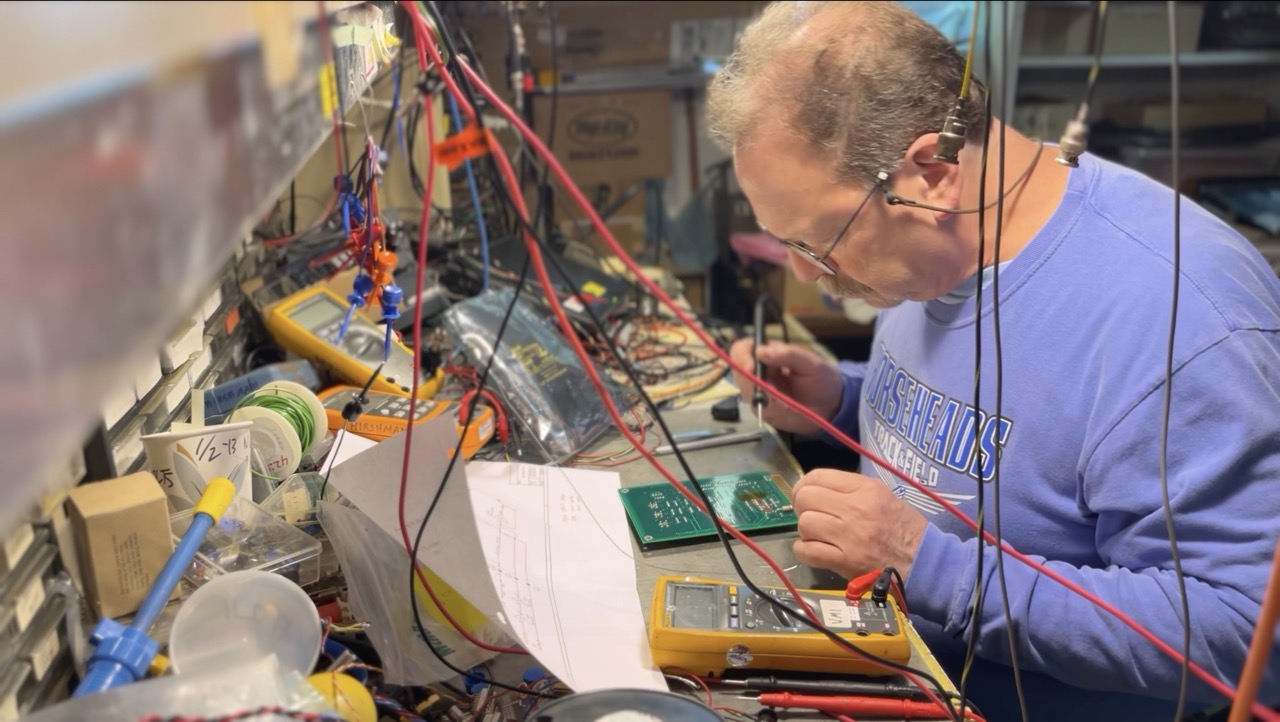

Electronics at the Coldest Temperatures

While mechanical systems provide structure and stability, FYST’s performance ultimately depends on electronics that must function reliably at temperatures just above absolute zero.

At CLASSE’s electronics shop, that work fits into a broader mission that spans multiple major scientific projects.

“There is a great deal of crossover between projects, people and their skills,” said John Barley of the CLASSE electronics group. “People who specialize in something do not have tunnel vision. The electronics staff has a lot to offer. Whether it is for FYST, the CMS project or Cornell’s accelerator complex, our electronics team is always pleased to contribute,”.

That cross-project experience is central to how CLASSE supports complex instruments like FYST. Very few facilities have the expertise needed to build electronics that can survive repeated thermal cycling and operate reliably at these temperatures, Niemack noted.

Sourcing the Unusual

Some components required for Prime-Cam cannot be fabricated in-house. They come from specialized vendors around the world, some new to Cornell, whose products must arrive on time and conform to strict performance requirements.

“There has been a lot of procurement work, with equipment being fabricated all over the world,” Niemack said. “We are getting things from Germany and from vendors that nobody at Cornell has ever used before. CLASSE procurement has been essential for helping us integrate those new vendors and get what we need.”

A key example is the superconducting coaxial cabling required for the instrument.

“These are electrical circuits that have to become superconducting and survive cooling to 0.1 Kelvin,” Niemack said. “CLASSE procurement helped us get those made and shipped, even with all the international hurdles.”

Preparing for Departure: Riggers and the High Bay

As Prime-Cam moves closer to deployment, the project’s focus shifts from design and fabrication to choreography. That transition begins with a carefully planned move from the Space Sciences building, where the instrument has been assembled and tested, to Wilson Synchrotron Laboratory across campus. There, in Wilson Lab’s high-bay space, CLASSE’s rigging crew will use overhead cranes and specialized equipment to perform a final “dry fit,” ensuring the multi-ton instrument can be safely positioned on the raft, then lifted and packed into its shipping container before the journey to Chile.

“We start by looking at the size and weight of whatever needs to be moved,” said Ed Foster, lead rigger at CLASSE. “Then we figure out what equipment we need.”

That equipment includes overhead cranes, forklifts, hydraulic jacks, machine skates, cribbing, pallet jacks and specialized trucks. The team then maps the route, accounting for tight corners, doorways, floor transitions and loading zones.

“Sometimes there’s a loading dock,” Foster said. “Sometimes there’s a roll-up door. And sometimes you have to get creative.”

Foster explains that Cornell’s historical buildings, with uneven floors and narrow hallways, can complicate moves like this. Foster’s team relies on steel plates to help bridge thresholds and machine skates to allow precise rotation. And in especially constrained spaces, hydraulic rams are used to inch loads through doorways.

“We have a really experienced team,” Foster said. “Each of these guys has more than 20 years of experience moving heavy equipment. They know what our equipment is capable of and how to do the job safely.”

The rigging crew also welded the aforementioned ‘raft’ that supports the Prime-Cam instrument, a contribution that will soon be installed nearly four miles above sea level in Chile.

“That’s pretty exciting,” Foster said. “Something we helped build is going to be set up on top of a mountain in another country.”

Experience That Carries Forward

For Niemack and the technical staff of CLASSE, FYST represents a demonstration of CLASSE’s collaborative strength and accumulated expertise.

“CLASSE has this incredible combination of people, and they all know how to work together on big, complicated builds,” Niemack said. “FYST is just one of several large projects here. That experience is what makes a project like FYST possible.”

As the telescope prepares for its high-altitude home in the Atacama Desert, its foundation has been shaped by the experts working behind the scenes at Cornell, whose achievements makes this global cosmology project possible.

FYST is a project of CCAT Observatory, Inc., a Cornell-led collaboration that includes a German consortium consisting of the University of Cologne, the University of Bonn and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching, and a Canadian consortium of universities led by the University of Waterloo.