History of Religion :

In Search of the Way, the Truth, and the Life

Volume 1

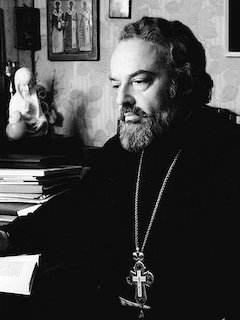

A strange sight was witnessed on the USSR Central TV on November 6, 1989: a deep-voiced, silver-haired priest of dignified appearance addressed viewers in a program called “Eternal Questions.” Such an event was unprecedented at the time, both for the Soviet audience and the state-run television alike. So much so that his ecclesiastical title—archpriest—was misspelled. What the audience could not have known at the time is that the speaker had been explicitly forbidden to use the word “God” in his 10-minute TV appearance. He spoke about a person’s inner world, the meaning of life, and eternal values. This first homily on the Soviet Central television can still be studied as a model of Christian kerygma, of how to express a man’s profound longing for higher meaning, something the priest has masterfully accomplished. The priest’s name was Fr. Alexander Men.

When religious freedom finally arrived in the Soviet Union, Fr. Alexander became a public figure, recognizable in every household throughout the USSR. Over the next two years, he delivered around 200 public lectures, speaking at Houses of Culture, universities, public schools, and even in stadiums. With his wide breadth of knowledge, he was able to get his message across to a broad audience of the Soviet people who were thirsting to hear the Good News, which had been largely out of their reach during their recent past dominated by Communist ideology. Still, the main audience in Fr. Men’s thirty years of priestly ministry was the Soviet intelligentsia—people of science, education, and culture.

On the early morning of Sunday, September 9, 1990, Fr. Alexander was on his way to Divine Liturgy when he was approached by a stranger. The stranger handed him a written note. (It is still a common practice in Russia to convey most intimate requests to a priest via a note.) Fr. Men put on his glasses, unfolded the paper and began to read. Suddenly, he was struck on his head with an axe by a second stranger from behind. Bleeding, he slowly continued on his way to church. “Who did this to you, Father Alexander?” asked a woman who came upon the bloodied priest. “No, it was no one. Just me.” He turned around and began walking back; as he reached the wicket gate of his house, he collapsed. His murder, unsolved to this day, sent shock waves across the whole country.

Alexander was born in Moscow in 1935 to secular, well-educated Jewish parents. His mother raised Alexander as an Orthodox Christian, after she had converted to Christianity and received baptism on the same day as her 6-month old son. It was the time of what became known as “the godless 5-year plan,” during which the Soviet authorities resolved to erase any mention of God. The anti-religious campaign was in full swing; even the calendar was transformed from a normal 7-day week into a 6-day week to make Sundays, along with religious holidays, fall onto work days. During that time, simply to believe was an act of bravery, and, since 1920s, a large portion of the remaining Russian Orthodox Church had gone underground in order to preserve their faith. From the early days and throughout his life, Alexander, through his mentors, stayed connected to the spiritual heritage of that part of the pre-Revolution Russian Orthodox Church best embodied by men such as the priest-saints Alexius and Sergius Mechevs and St. Nectarios of Optina. Already at the age of 12, young Alexander purposed in his heart to become a priest.

In 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, Men, who was fond of biology, began his university studies in the Moscow Fur-and-Down Institute. The Institute was transferred to the city of Irkutsk in Siberia in 1955. In 1958, when Alexander was set to graduate, he was expelled without a degree from the Institute because of his religious beliefs. The combination of Alexander’s outstanding intellect, superb social skills, and deep Christian faith was a bête noire for the Soviet system. Yet God’s hand was on the life of the future “apostle to the Soviet intelligentsia”: one month after he was expelled, Alexander was ordained a deacon; two years later, he graduated from the Leningrad Theological Seminary and was ordained a priest. In 1965, Fr. Alexander completed his studies in Moscow Theological Academy, done mostly through independent study, something he continued to pursue all his life, to his last day.

To put Men’s writings into context, we must understand what motivated him to become a voice for Christianity to his own people. The Soviet culture was categorically anti-religious, viewing any type of faith as its ideological adversary. All educational and social institutions upheld and coercively indoctrinated the materialistic creed that “science had proven that there was no God.” Materialism and atheism reigned uncontested in all quarters of society; any public mention of God, other than in a derogatory way, was considered scandalous. In the face of these universal anti-religious sentiments, there was Alexander Men, with his deep convictions, inner strength, wide erudition, and his unwavering belief in the power of Christ’s eternal message to reach his ideology-laden contemporaries.

Already as a college student, when Alexander had to take the State Examinations on political economy and Marxism-Leninism, he demonstrated his erudition and knowledge of these topics but refused to kowtow to the prevalent views or hide his Christian convictions. Needless to say, he had to suffer the consequences, but, providentially, his expulsion from the university solidified his path to priesthood and the life of ministry. During the 1960s, priests were limited to “church confines” with any activity outside the church walls strictly forbidden and all the happenings inside being closely monitored by the state security agents. The main focus of Fr. Alexander Men was to reach people with the message of Christ, for which he constantly sought new and creative ways. Fr. Alexander’s scholarship is marked by a deep understanding of the Christian message and how to convey this message to his main audience—people educated in the atheistic Soviet system. Because he could not publish in his home country, all his major writings were first published under a pseudonym abroad.

The breadth of Men’s views is sometimes confused with him being indiscriminate or insufficiently Orthodox in his convictions. However, Fr. Alexander’s living out the words of St. Paul, “I have become all these things to all, so that by all means I might save some” (1 Cor 9:22), points to the true source of his breadth. His numerous spiritual children and millions who have been reached with the profound message of Christianity remain a living legacy to his labors. Furthermore, the leading hierarchs in the Russian Church, men such as Metropolitan Anthony of Sourezh and Patriarch Kirill, highly praised Fr. Men’s works and his character as a priest.

Fr. Alexander’s own voice in his defense can be heard in his response to an anonymous critical letter by another priest. This response, given as an Appendix to Vol. 1, showcases Fr. Men’s scholarly approach to biblical studies and outlines his way of thinking by demonstrating that his approach does not constitute a novelty in the Church but, rather, extends the work of ancient Church Fathers in general and, in particular, the tradition of scholarship exhibited at the heyday of the Russian Church prior to the Bolshevik Revolution (and later continued by the Russian emigration, e.g., in St. Sergius Institute in Paris). Fr. Men’s works do not produce final answers to many of the questions being posed; he only exemplifies how to boldly engage the world with the goal of “unpacking” Christianity as a sanctifying force transforming humanity—an effort that requires prayerful and diligent work of today’s Christians. As such, Fr. Alexander Men was realizing Fr. George Florovsky’s famous thesis of “forward, to the Fathers!”

The first volume of History of Religion: In Search of the Way, the Truth, and the Life, this book, is a condensed version of Men’s magnum opus under the same title, which consists of seven volumes. Men’s original work was more academic in nature even though it was written for the broad Soviet audience in mind. Fr. Alexander always prized a broad education and had plans to publish a more accessible version of his History of Religion. His untimely death stood in the way of his plans; this work was continued by his friends and family who condensed each of the seven volumes into the seven chapters of the present book.

The second volume, The Paths of Christianity, provides a daring overview of the history of the Church in the first millennium, ending with the Baptism of Russia. In it, Fr. Men presents the history of the Good News spreading and taking root in medieval cultures. He does so without glossing over the more controversial aspects of Church history, adopting, so to speak, the vantage point of the Heavenly City of St. Augustine. The second volume is based on Fr. Alexander’s (incomplete) book The First Apostles (Chapter 1) and his notes on the history of the Church (Chapters 2 and 3) that he first prepared when he was still a young man, around the age of twenty. Similar to the first volume, Volume 2 acquired its final shape at the hands of Fr. Alexander’s friends who continued his work posthumously. As textbooks, both volumes are conceived to be accessible to entry-level undergraduate students.

As the translator, I felt that there was a considerable value in incorporating references to all the citations and expanding footnotes found in the original seven volumes and Men’s The First Apostles (but not available in the Russian edition of these textbooks). At times, when Fr. Alexander was paraphrasing rather than directly quoting his sources, a preference was given in this translation to quoting the original, indicating with square brackets and ellipses whenever the text was modified in some way. An index was also included to help those who want to use these books as a reference.

Since Fr. Alexander was a biblical scholar himself, who knew biblical languages and translated certain biblical passages directly from the original, none of the quotations of the Bible follow a particular English translation unless explicitly stated otherwise.

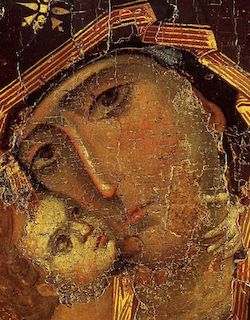

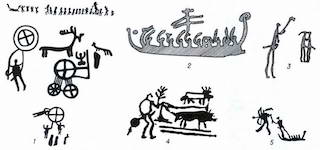

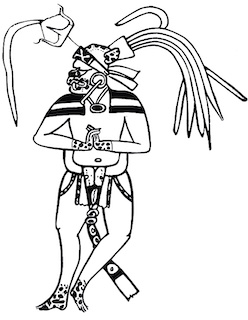

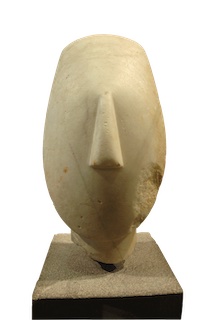

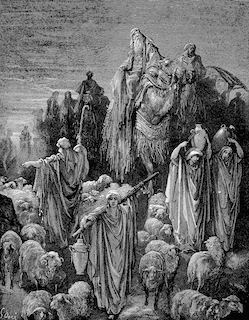

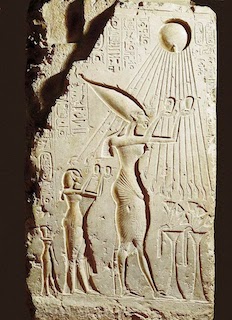

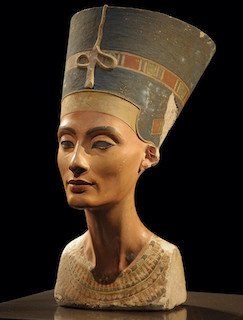

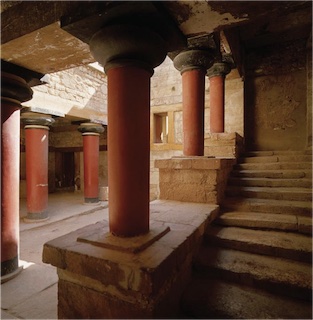

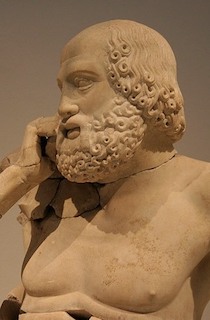

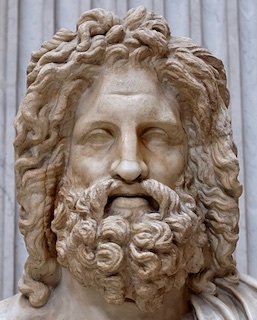

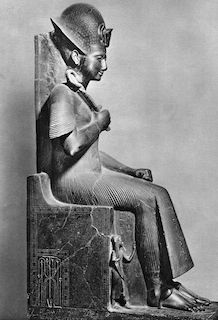

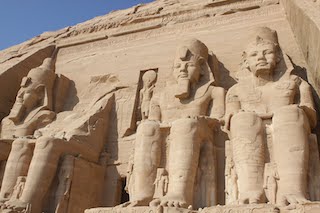

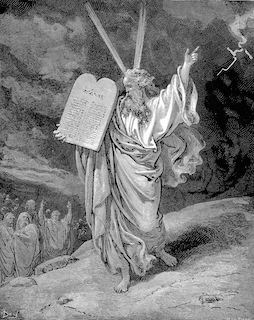

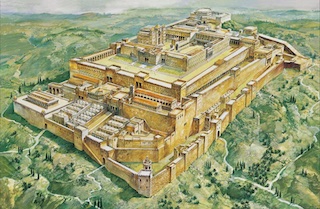

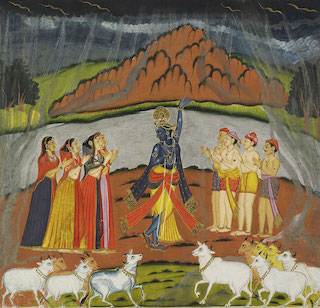

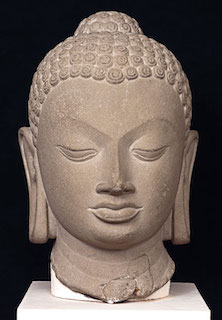

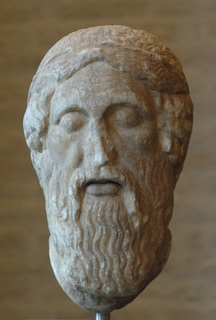

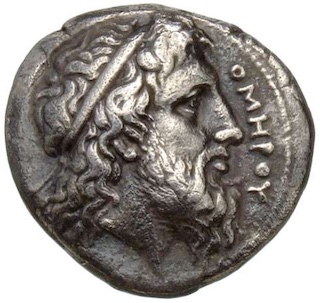

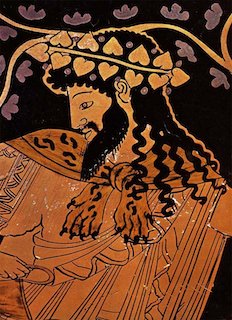

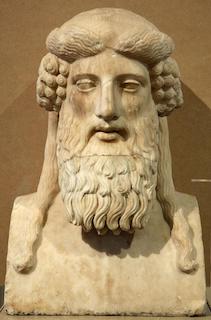

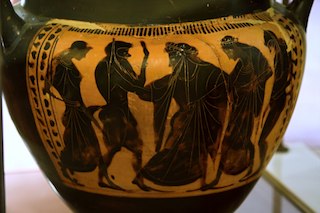

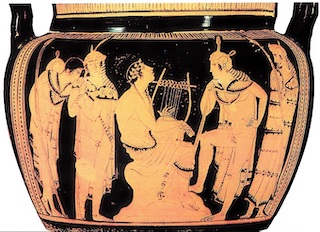

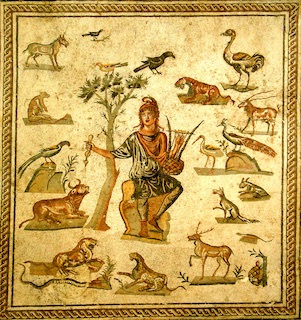

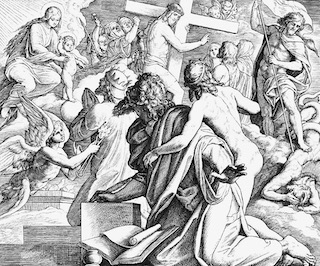

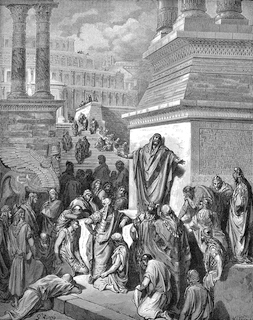

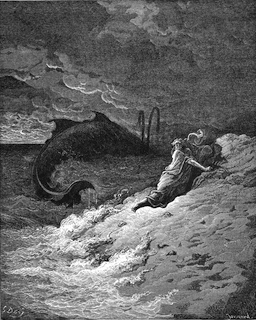

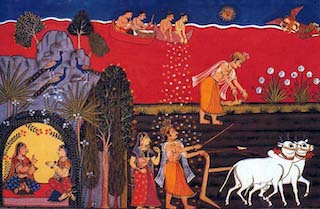

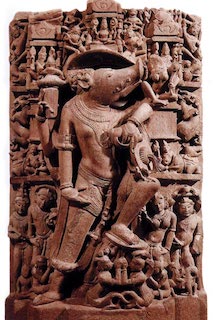

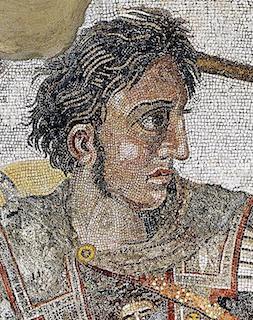

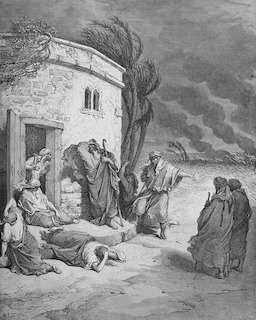

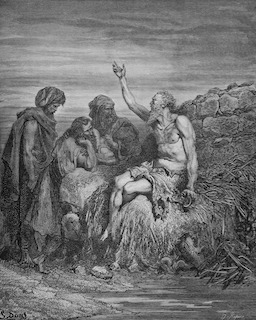

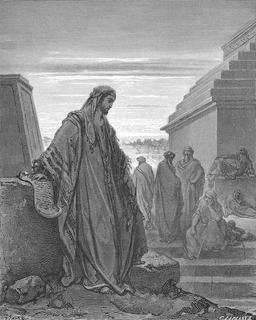

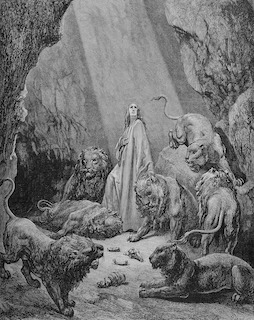

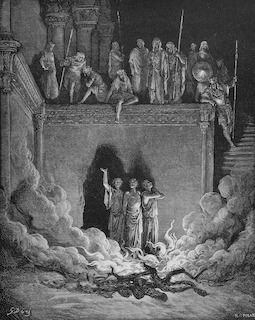

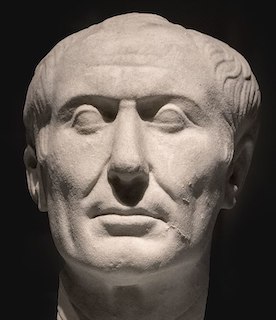

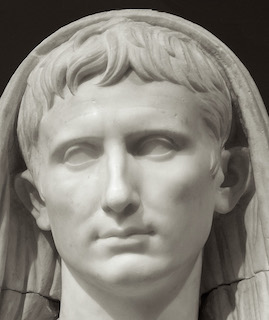

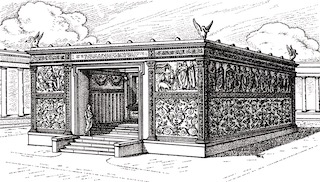

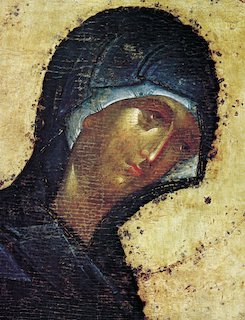

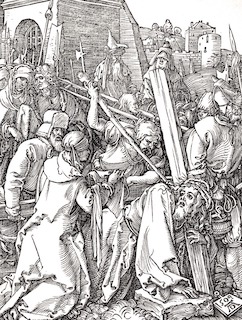

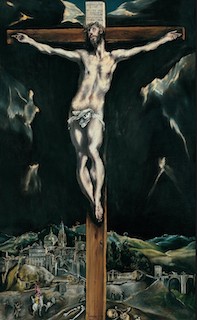

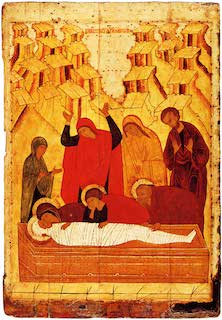

Fr. Alexander placed much importance on visuals to reach the audience with his message. Most of the illustrations found in these two volumes follow the Russian edition, but, in some cases, they have been replaced with thematically suitable alternatives. The original dating of some illustrations and artifacts has been changed to reflect the more recent sources for dating.

Like the Russian version, each of the two volumes has a section with suggested Further Reading. Whenever a suggested book was not available in English, this translation offers an alternative reading covering the same area. However, a more glaring gap exists in the reading list for the second volume, The Paths of Christianity, which, in its Russian version, includes the works of many excellent church historians of the pre-Revolution era and the first half of the 20th century (e.g., Vasily Bolotov and Anton Kartashev), experts in Eastern Church patristics (e.g., Archim. Cyprian Kern), and Soviet researchers of Byzantium (encyclopedias on Byzantine culture and writings)—the sources available only in Russian today.

On a personal note, as the translator, I have come to appreciate Fr. Men’s works in my own spiritual journey. My hope, as well as the motivation for taking on this task of translation, has been that these books will provide some wisdom and guidance in how to better navigate, reconcile, and integrate the deep spiritual heritage of humanity and of the Church with many of the challenges that face the modern world and society.

I want to acknowledge the help of many friends and family who contributed to improving this translation. Samuel Carthinhour, Waymon Lowie, and Maury Tigner spent countless hours poring over and improving my at times rugged translation. Holly Dzikovski, Matthew Andorf, and Gregory Fedorchak made many useful remarks on Volume 1. I am indebted to Hugh and Arlene Bahar for many excellent suggestions on how to improve both Volumes 1 and 2. Finally, this work would not have been possible without the continued love and support of my entire family: my wife Natalie, and sons Samuel, Alexander, and Matthew. Whenever any of the text reads fluidly, special thanks go to Natalie, whose graceful touch has enlivened not only this translation but imbues every day of my life with meaning and color.

Ivan Bazarov

May, 2021

Alexander Men’s scholarly legacy is striking in its versatility and breadth of scientific outlook. When looking back at his work in the areas of biblical scholarship, religious studies, cultural history, and literature, one cannot but be amazed by the vast volume of his writings. A prominent figure of the Russian Orthodox Church, a biblical scholar, a theologian, and a preacher, he accomplished in his short life the amount of work that rivals that of a group effort.

His deep academic research was combined with his active life as a preacher. He lived his life at its fullest: serving as a parish priest, writing books and articles, lecturing at schools and universities, and appearing on radio and television. Fr. Alexander gave himself fully to serving God and people.

The future pastor was born in 1935. Even in his early youth, Alexander already realized his calling to become a priest. During his school and University years, he voraciously acquired and broadened his religious knowledge. We should not forget that his youth was lived in a time of rampant atheism when believers were under extreme pressure from both the state and society. Preserving and protecting faith under those conditions was nothing short of a moral feat.

All of Alexander Men’s scholarship and priestly activities were distinguished by his inner dignity. A man of encyclopedic knowledge, he was always open to the great Truth. The main work of his life is a series of books on the history of religion, as well as a book about Jesus Christ, The Son of Man. In them, Fr. Alexander traces a spiritual history of mankind—its search for the meaning of life. In his works, he showed that these searches are essentially an ascent to Truth, that is Christ.

A prominent biblical scholar, Alexander Men was dreaming of writing a textbook on the history of religion. The priest’s tragic death in 1990 put an abrupt stop to his plans. The ambitious project was never completed, but Fr. Alexander’s books and his priceless scholarly archive have remained. The work to create the textbook was continued by Alexander Men’s friends and family.

The textbooks, presented to the readers under the general title of History of Religion, are based on the materials of the books written by Fr. Alexander. The compilers considered it their duty to preserve his inimitable style—so memorable to everyone who had the good fortune of hearing this remarkable man speak.

The first book, In Search of the Way, the Truth, and the Life, explores the origins of religion and early beliefs—from prehistoric mysticism to the idea of a living God. The book recounts the emergence of the ancient Israel’s religion that gave the world the liberating fire of Light and Truth, the coming of the Messiah, His earthly life, and the victory over death. We learn that the spiritual quest of humanity was embodied in the person and teachings of Jesus Christ, that His birth, for the most profound reasons, was the beginning of a new era—the era of the triumph of Truth.

The second book, The Paths of Christianity, covers the first millennium AD. It outlines the spread of Christianity, the missionary activities of the disciples of Jesus, the first Christian Empire, the Church Fathers, the causes of the Great Schism, and the Baptism of Russia. The author reveals the mystery of thousands upon thousands joining the Church through love, which is extremely important today for the spiritual revival of Russia.

Alexander Men does not idealize Christianity—he shows the real picture of the Church’s life, without glossing over its dramatic sides: dissenting views, schisms, heresies, and outbursts of fanaticism. The author’s moral principles compel him to present a fair and unprejudiced account of these topics.

Religion has always been at the core of human spirituality. In search for God, humanity had trod many paths—from world-denying mysticism to God-denying materialism. At the end of this journey came, using the words of the Bible, “the fullness of time”:[3] the world approached the Revelation of the greatest mystery, and humanity was granted the path to a perfect life.

Yet, people were granted the freedom to choose whether to accept the Gospel or to reject it. This freedom remained inviolable, sealed by the historical humiliation of Jesus of Nazareth, His death on the cross, and His utterly paradoxical teaching, all of which required an act of faith to be embraced.

In vain, people sought to impose their own standards onto Christianity: some demanded signs, others—philosophical proofs. But the Church spoke through the mouth of the Apostle Paul: “We preach Christ crucified, to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks foolishness” (1 Cor 1:23).

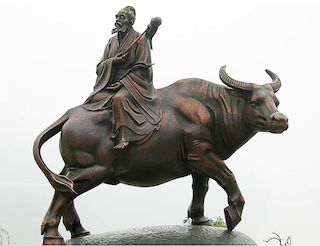

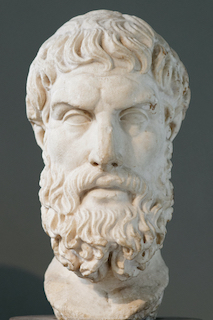

And yet the Gospel entered the history of mankind not as a human but as a Divine message. Having won over many, it has remained a stumbling block and foolishness to others. Some, having received it, stumbled afterwards. Yet the world had nowhere else to turn but back to myths and illusions that had captivated the human spirit in the pre-Christian era. A departure from Christ inevitably meant a return to Buddha or Confucius, Zarathustra or Plato, Democritus or Epicurus.

The author of Ecclesiastes was right when he wrote, “There is nothing new under the sun” (Eccl 1:9). When one examines any of the teachings that have emerged over the last twenty centuries, it becomes evident that they are merely a repeat of what came before.

Relapses into pre-Gospel consciousness are common even among Christians. Such reversions manifest themselves in detached spiritualism,2 authoritarian intolerance, and magical ritualism. This is easy to understand: two thousand years is not nearly enough time to overcome “paganism” and accomplish the goals that the God-Man has set before humanity. And these goals are truly absolute and inexhaustible. It can be said that the “leaven”[4] of the Gospel has just begun its transformative action.

∗∗∗

History does not know a single nation that has been completely devoid of religious beliefs. Even atheists cannot be considered unbelievers in the true sense of the word. The ideological myths that they take for granted are essentially a religion in disguise. As a result, atheism has its own “beliefs” that aspire to bring some sense into the apparent absurdity of life, with the goal of reconciling people to an emptiness that they by their very nature cannot accept.

There is something both tragic and mystifying in the atheist’s aspiration to hide from the abyss of the indifferent Universe, from the cold and empty heavens. The atheist experiences not only fear and anxiety, but also an unconscious pull toward the very things that materialism vehemently denies—Meaning, Purpose, and intelligent Provenance of the cosmos.

The human soul has always sought beauty, goodness, and divine qualities that are worthy of worship. Should this be dismissed as a meaningless self-illusion? Isn’t it more natural to admit that, just as a physical body is connected to the material world, so the soul gravitates toward an unseen Reality? And is it not significant that when a person turns away from that Reality, superstitions and secular3 “cults” take religion’s place instead? In other words, turning away from God inevitably leads to some form of idolatry.

It is bad enough when places of worship are vacant, but it is even worse when the buildings are full while the hearts of those who come remain empty. Keeping external rituals is not always the best indicator of a faith’s well-being; nor does low attendance, in itself, signal a decline of the faith. Moreover, outward forms of church life have always changed in the past and will continue to do so in the future.

Even having lost God, people passionately seek the absolute. Religion remains the most personal form of human activity. This is precisely why it is in religion that the human spirit, lost in the labyrinths of civilization, again and again finds a solid foundation and inner freedom. The true self, as the highest manifestation of what it means to be human, will always find a stronghold in the Sacred.

The famous physicist Max Born, speaking of the abyss into which civilization is heading, stressed that only religious ideas can restore health to human society. “At the present time,” he wrote, “fear alone enforces a precarious peace. However, it is an unstable state of affairs, which ought to be replaced by something better. We do not need to look far in order to find a more solid basis for the proper conduct of our affairs. It is the principle that is common to all great religions and with which all moral philosophers agree; the principle which in our own part of the world is taught by the doctrine of Christianity.”[5]

Those who speak of the “death of religion” are either short-sighted, intentionally blind to reality, or simply misinformed.

Today, more than ever, the words of the Apostle Paul, spoken two thousand years ago, ring true: “We are considered as dying, and yet we live on” (2 Cor 6:9).

What is faith? Scientists and theologians have defined it differently and often in contradictory ways. For example, religion has been associated with a sense of moral duty (Kant), a sense of dependence (German theologian Schleiermacher), and even with the fear of the unknown (English thinker Russell).

We will not entertain the ideas of the Lumières (“Enlighteners”) that religion is the product of deliberate deception. Atheists themselves have long abandoned this view. But much more stubbornly they held on to another 18th-century concept: that religion is the product of ignorance of primitive men who did not know the laws of nature. Such statements are still commonplace in anti-religious literature. However, faith lives on even when human knowledge about nature deepens; it is practiced by those at the highest rungs of the intellectual ladder.

The specific beliefs of a people group are largely influenced by historical, geographical, and ethnic factors. Yet religion transcends them: this explains the remarkable spiritual unity that often arises among peoples separated by psychological, racial, and historical barriers. Conversely, nations can share ethnic, economic, historical, and geographical commonalities and yet differ significantly in their spiritual outlook. “The ultimate barriers between people,” writes the English philosopher and historian Christopher Dawson, “are not those of race or language or region, but those differences of spiritual outlook and tradition which are seen in the contrast of Hellene and Barbarian, Jew and Gentile, Muslim and Hindu, Christian and Pagan. In all such cases, there is a different concept of reality, different moral and aesthetic standards, in a word, a different inner world. Behind every civilization there is a vision—a vision which may be the unconscious fruit of ages of common thought and action, or which may have sprung from the sudden illumination of a great prophet or thinker. … But while an intellectual or spiritual change will produce far-reaching reactions upon the material culture of a people, a purely external or material change will produce little positive effect unless it has some root in the psychic life of a culture. It is well known that the influence of the material civilization of Modern Europe on a primitive people does not normally lead to cultural progress. On the contrary, unless it is accompanied by a gradual process of education and spiritual assimilation, it will destroy the culture that it has conquered.”[6]

A culture that abandons its religious foundations invites decay. True cultural flourishing, by contrast, is impossible without a vibrant spiritual life.

What would the history of Israel be without the Bible, or what would European civilization be without its influence? What would Western culture be without Catholicism, Indian culture without its religions, Russian culture without Orthodoxy, Arab culture without Islam? Crisis and decadent phenomena in culture, as a rule, are associated with a weakening of its religious impulse, which leads to degradation and stagnation in creativity.

Most definitions of religion speak almost exclusively of the psychological prerequisites of faith, but we are interested in its core essence.

Religion is the mind’s response to Existence; the whole question is how to define Existence itself. Materialism reduces it to unintelligent causes, whereas religion sees an ultimate Divine Essence as its foundation and recognizes itself as a response to the manifestation of this Essence.

Material existence is apparent to us—but how can we apprehend the Existence of the Divine? Since the Ultimate Existence cannot be seen or heard, how can we know whether It is real?

Faith is assurance of a reality experienced internally and intuitively, not based on external facts or formally logical proofs.

The study of nature in many ways relies on intuition; the role of intuition is even greater when it comes to understanding the essence of existence itself. The great Catholic thinker Thomas Aquinas said that if man’s path to God had lain through abstract philosophical thinking, then faith would have been accessible only to the tiniest minority. In reality, we observe that spirituality is inherent to both an illiterate peasant in India and a scientist in Europe who has reached the pinnacles of modern knowledge. This is possible precisely because spiritual knowledge is a product of a living intuition.

In its most general terms, religion can be defined as an experience connected with the awareness of the presence of a certain Highest Principle in our lives that guides our existence and gives it meaning. This experience is acquired through a direct awareness of the Supreme, which reaches the same level of authenticity as self-awareness. And this experience cannot be distilled into notions and symbols unless it is first processed intellectually.

Plotinus, an eminent philosopher of the Hellenistic world, put it like this: our awareness of God comes “not by way of reasoned knowledge… but by way of a presence superior to knowledge.”[7]

Religious experience cannot be reduced to any other dimension of human existence and is best defined as a sense of awe. Einstein once said: “the most beautiful thing we can experience is the Mysterious…. He to whom the emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand wrapped in awe, is as good as dead…. To know what is Impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest Wisdom and the most radiant Beauty—this feeling is at the center of true religiousness.”[8]

The most important thing is that a person through and in oneself can discover an “other” type of existence, distinct from nature. And the more intense and perfect is the process of human self-discovery, the more authentic this unseen world emerges being. “To mount upward to God,” said the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel, “is to enter into oneself, moreover, into the depth of oneself—and to transcend self within.”[9]

Our spiritual “self” is a window into the world of the universal Spirit. Just as harmony with nature is the basis of one’s life on earth, so, too, does connection with the Supreme determine one’s spiritual existence. Henri Bergson (French philosopher, 1859–1941) saw the mystical experience not only as a means of a breakthrough to the union with the Divine, but also as a key to further development of humanity.

The question of the origin of the Universe has always captivated mankind, especially people of science. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Enlightenment thinker, 1712–1778) wrote over two hundred years ago: “The mind is confused and lost amid these innumerable relations, not one of which is itself confused and lost in the crowd. What absurd assumptions are required to deduce all this harmony from the blind mechanism of the matter set in motion by chance! In vain do those who deny the unity of intention manifested in the relations of all the parts of this great whole, in vain do they conceal their nonsense under abstractions, coordination, general principles, symbolic expressions, whatever they do I find it impossible to conceive of a system of entities so firmly ordered unless I believe in an intelligence that orders them. It is not in my power to believe … that blind chance has brought forth intelligent beings, that that which does not think has brought forth thinking beings.”[10]

Einstein is known to have admitted: “My religiosity [is] deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a Superior Reasoning Power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible Universe.”[11]

The materialists put in the place of this Superior Reasoning Power something they refer to as “matter.” But if reasoning power is inherent to this “matter” then it is no longer matter.

At first, the technical advances and scientific theories of the 19th century purported to confirm materialism—invariably the view of science communicators, philosophers unversed in science, and scientists who knew little philosophy. In the 20th century, materialism had to make a concession under the influence of discoveries in physics and biology: “matter” became a term to describe any objective reality.

But the main inner “nerve” of materialism remained unchanged. That nerve was the denial of God. To the forefront came the emotional pathos of theomachism, or God-fighting, rather than problems of science and philosophy.

Marx’s protest against religion was motivated by his political struggle, inasmuch he identified religion with extreme conservatism. Lenin’s atheism was just as highly emotional, devoid of any “scientific” character.

The “scientific worldview” referred to by atheists is in itself a rather contested phenomenon. There is no evidence that all of existence is amenable to scientific analysis. One’s worldview always has its roots grounded in faith or conviction that goes deeper than the scientific level.

No longer do people look for answers to questions concerning chemistry or geology in the Holy Scriptures, nor does Christianity make itself dependent on constantly changing scientific insights. People sought God at all times: first, when they considered the Earth to be flat, then, as a planet anchored at the center of the solar system, and later, when they put the Sun in that central place.

The main point of contention between materialism and religion—the question of the origin of the Universe—lies outside the realm of experimental science. Materialists claim that the Universe is infinite in both time and space. But what scientific experiment can possibly penetrate that which is infinite and unoriginate? Are we simply to accept the materialists’ claim that a creative Origin outside spacetime could not have possibly been the cause of the infinite Universe?

Since the Middle Ages, some theologians have expressed the opinion that the Universe might not have had a “beginning” in time, for God’s creative act must be timeless4 by nature.

The more natural science progresses, the clearer it becomes that learning about the very foundations of the world lies beyond science. It is not surprising, therefore, that the majority of the foremost scientists who enabled scientific progress found the idea of God, the Creator of the Universe, full of deep meaning and vital significance.

Personal spiritual experience, paths of reason, and advancement of science can all lead to the highest Reality.

“The most immediate proof of the compatibility of religion and natural science,” wrote Max Planck (German physicist, 1858–1947), “is the historical fact that the very greatest natural scientists of all times—men such as Kepler, Newton, Leibniz—were permeated by a most profound religious attitude.”[12]

Carl Linnaeus, the creator of biological taxonomy, stated that he saw the power of the Creator in the diversity of living beings. Lomonosov (Russian polymath, 1711–1765) called faith and knowledge the two “daughters of one Almighty Parent.”[13] Pascal, Newton, and Faraday were all theologians. Pasteur professed that he used to pray in his laboratory, and Francis Bacon believed that “a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism, but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion.”[14]

The Divine Reality remains intimate and does not overwhelm people with overbearing evidence, thus preserving our freedom before God. Getting to know God is a gradual process that takes place in strict accordance with the person’s readiness for the mystical Encounter. God, as it were, remains hidden from direct perception. Step by step, He comes into people’s consciousness through nature, love, the sense of mystery, and the experience of the Sacred. This also explains the historical diversity of religions, which reflects the various stages and levels of knowing God.

Nevertheless, it is appropriate to discuss the properties shared by various religions. These reflect both the unity of human nature and the kinship of experiences that evoke the sense of the Supreme and the thought of Him. Although faith can be obscured by egoism, self-interest, and primitive fear, its true core—the sense of awe—is shared by both a heathen and a follower of one of the world’s major religions. At some point in life, even an atheist partakes of this feeling and experiences a closeness to an “unknown God” (see Acts 17:22–23).

A special spiritual and moral inner preparation is necessary in order to come into contact with the Divine. “Never can the soul have a vision of the First Beauty unless it itself be beautiful,” Plotinus wrote, “Therefore, first let each become godlike and each beautiful who cares to see God and Beauty.”[15] That is why the great saints were “God-seers”—their souls became an instrument for knowing God. And millions of pure hearts who sincerely loved the Truth have followed in their footsteps. The difference between knowing God for religious geniuses such as Francis of Assisi, Teresa of Avila, Meister Eckhart, Seraphim of Sarov, and the Optina elders on one hand, and ordinary people on the other, is as follows: the former sought the Divine life with their whole being and became its bearers; whereas the latter experienced encounters with God as occasional flashes of lightning, separated by long periods of darkness. The former rose to such heights of contemplation that were beyond all power of words to describe. Therefore, when they attempted to convey what they had comprehended, they were able to express only a tiny part of their actual experience.

An encounter with God takes place in the life of every person, and religious experience is therefore a universal theme. The outcome of this encounter differs depending on whether a person is ready for the opportunity or passes it by. The calling of the Unseen is often perceived through a prism of prejudices and distrust of anything that falls outside the everyday life experiences. Sometimes this call is heard by a lethargic and limited soul or one subject to primitive interests and goals; in both cases this call is to remain the “voice of one crying in the wilderness” (see Mt 3:3; Mk 1:3; Lk 3:4; Jn 1:23). For, indeed, the soul that did not respond to the Divine call is a spiritual desert.

“I had lived only when I believed in God,” wrote Leo Tolstoy in his Confession, “Then, as now, I said to myself: as long as I know God, I live; when I forget, when I do not believe in him, I die.”[16] A drastic change in the mindset of a believer due to his encounter with Eternity is reflected in his entire being and his every action. The Prophet Isaiah or Buddha, Muhammad or Savonarola, Gus or Luther, and other spiritual leaders radically transformed their social milieu, and these changes have endured for centuries.

“The history of all times and nations,” said Max Planck, “teaches us that exactly in the naïve, unshakable belief, furnished by religion in active life of believers, originate the most intense motives for the most significant creative performance, not only in the field of arts and sciences but also in politics.”[17] Indeed, it is impossible to overestimate the inspiring role of faith in the lives of great thinkers, poets, artists, scholars, and reformers.

The believer does not close his eyes to the evil of the world, but at the same time, he refuses to recognize it as invincible. He can confidently say along with Albert Schweitzer (protestant theologian, 1875–1965): “My knowledge is pessimistic, but my willing and hoping are optimistic.”[18] This is why, in spite of everything, our simple human life can sparkle with colors of eternity.

The word “religion” comes from the Latin verb religare, which means “to bind.” It is the force that binds the worlds, a bridge between the created and the Divine spirits. Strengthened by this connection, a person becomes a co-participant in the creation of the world. God does not enslave people, nor does He coerce them to go against their will, but, on the contrary, He grants them complete freedom, including the ability to reject Him and seek their own ways.

The fullness of existence, not abject subservience, is brought about by union with God. The historian of religion Otto Pfleiderer wrote: “Man is not afraid that, by this free obedience or surrender to God, he will lose his human freedom and dignity; but, on the contrary, he is confident that, in the alliance with God, he will achieve freedom from the limitations and fetters of surrounding nature, and those worse limitations and fetters of nature within us…. As Seneca said long ago: to obey God is to be free.”[19]

Life in faith is inseparable from the struggle for the triumph of good, the struggle for all that is light and beauty; it should not be a passive expectation of “manna from heaven,” but a courageous confrontation with evil. Religion is the true foundation of moral life. We find no foundation for ethical principles in nature.5 According to a witty remark by the biologist Thomas Huxley,[20] the thief and the murderer follow nature just as much as the philanthropist (and the former to a greater degree!). An objection could be made that morality is dictated by one’s duty to society. Yet the very realization of this duty is, in turn, nothing more than a moral conviction. On the other hand, the denial of meaningful existence, the denial of God, paves a path to the triumph of unbounded egoism and infighting.

Often, people pose a painful question: why is there so much evil in the world? How do we reconcile the revelation of the Creator’s omnipotence and God’s goodness with the evil reigning in the world? Pain and death, to which all living creatures are subject, imprint their terrible mark on all our lives. Death engulfs life. Chaos overwhelms orderliness. Processes of creation are being constantly undermined by the forces of destruction.

Christianity agrees that existence itself bears the traits of imperfection and that cosmogenesis6 is inseparable from the conflict of the two polar opposing principles. The Bible, however, when speaking of the world as God’s creation, views the Universe as something dynamic, something being brought to perfection. The Old Testament knows about the forces of Chaos, but it does not deify them. Instead, it sees only a created principle in them that opposes the Creator’s intent. According to the Bible, God cannot be the source of evil. Evil is a violation of the divine plan by the creation, and not merely “a delay on the road to perfection”[21] as Ephraim Lessing (German author, 1729–1781) put it.

The images of the monsters of Chaos and Satan, which we find in Scripture, signify that a catastrophe has occurred in the spiritual world. It was there that the hotbed of demonic “self-will” arose, a revolt against harmony, which echoed throughout all nature. The apostle Paul says, “The whole creation groans and labors with birth pangs together until now” (Rom 8:22). “For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it” (Rom 8:20). These words point to the dependence of the present state of nature on the universal Fall. Could the irreversible nature of physical time itself with its relentless cruelty be the affliction imposed on the Universe? After all, the Apocalypse predicts that there will be no time in the coming Kingdom (Rev 10:6).

This view may seem to be a denial of Divine Omnipotence. But Christianity teaches that any act of God in relation to the world constitutes self-limitation on His part or, as the Church Fathers put it, the kenosis (“emptying”) of the Absolute. It is precisely this kenosis that leaves room for freedom in the creation without distorting the image of the Creator.

The Russian religious philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev writes: “A non-religious mindset might question the deed of God and seize upon this, that it might have been done better, had God happened to enforcedly create the cosmos, creating people incapable of sin, all at once to bring being into that perfect condition, in which would be no suffering and death, and people would incline only towards the good. This rational sort of plan to creation dwells wholly within the sphere of human limitedness and it does not raise into awareness the meaning of being, since the meaning is bound up with the irrational mystery of the freedom for sin. A forced and compulsive outward extirpation of evil from the world, along with the necessity and inevitability for the good—this would ultimately be in contradiction to the dignity of every person and to the perfecting of being, hence a plan, not corresponding to the intent for Being as absolute in all its perfections. The Creator did not create amidst a reinforced necessity a perfect and good cosmos, since such a cosmos would neither have been perfect nor good at the core of its foundation. The foundational basis for perfection and good—consists in freedom, in the freedom of love towards God, in the freedom of a co-uniting with God, and this character trait of every perfection and good, of every being renders inevitable the world tragedy. In accord with the plan of the creation, the cosmos is given as a task, as an idea, which freedom of the creaturely soul ought to creatively realize.”[22]

Creation is Logos7 overcoming Chaos oriented towards That-which-is-to-come. Thus, struggle is the law of the creation of the universe, the dialectic of its coming into being.

According to the views of many ancient peoples, the Creator is a craftsman shaping utensils necessary for life with His own hands. For example, some Egyptian reliefs depict the god Khnum making man with the help of a potter’s wheel. In India and Greece, the world was believed to be born out of the depths of the Deity.

Only biblical teaching has opposed all shades of paganism and pantheism8 with the idea of creation as an act of Divine Will, Reason, and Love. This act is a link binding the Absolute with all of creation. According to Scripture, the creative power of the Word of God, having summoned the creation from nonexistence, constantly nourishes it and maintains its existence.

The Bible pictures cosmogenesis as an ascent from the lower to the higher state, from inorganic matter to highly organized beings—humans. Naturally, this concept of the Universe’s origins was expressed in a form that corresponded to the level of knowledge and mentality of that distant era when the book of Genesis was being written. However, the creation imagery is not simply a reflection of ancient modes of thought: the sacred author was expressing a mystery, which by its very nature is best conveyed symbolically. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.”[23] These words are not a statement of scientific fact, but rather are a representation of reality using the language of Myth in the highest and most sacred sense of the word. In order to convey the incomprehensible, abstraction must give way to picture, image, and symbol—elements inherent to the language of all religions.

Intuitive insights in the form of a myth often anticipate the development of science. It is in the Bible, rather than in Greek, Babylonian, and Indian writings, that we encounter for the first time the concept of the world as History, Becoming, and Process. The myths and philosophical systems of Antiquity essentially stood outside the categories of past and future; they viewed the Universe, replete with gods, humans, and lower beings, to be in an eternity of repetitive cycles. It was in the prophets of the Bible that the world’s inner yearning for perfection first came to light.

When Darwin’s theory of evolution came onto the scene in the 19th century, opponents of religious faith enthusiastically adopted Darwinism as their credo, vehemently attacking the biblical “days of creation.” As a result, Darwinism became something of a bugbear to pious believers provoking panic among them.

One of the first to realize the genuine religious significance of evolution was none other than the grandfather of Charles Darwin—the poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin. “The world itself,” he writes in his Zoonomia, “has been gradually produced from very small beginnings, increasing by the activity of its inherent principles… What a magnificent idea of the infinite power of the great Architect! The Cause of causes! Parent of parents! The Being of beings! For if we may compare infinities, it would seem to require a greater infinity of power to cause the causes of effects, than to cause the effects themselves.”[24] These words aptly sum up the essence of the Christian approach to evolution. According to the Bible, the very existence of the world depends on the Creator who sustains the Universe by His creative power; hence the concept of the “ongoing creation.”

According to the Christian understanding, evolution is not simply a movement forward, but also a return of the created order to the ways originally set out by the Creator. It reveals the purpose of the evolutionary development aimed at creating humanity whose calling is to spiritualize the world, opening it to new creative acts of God. This is the meaning of true progress from the point of view of faith. Science, on the other hand, can only study the forms and stages of nature’s formation, and as such, it is still a long way from unravelling the entirety of factors governing evolution.

Following the emergence of the basic building blocks of matter, the second miracle of nature was life, which Erwin Schrödinger (Austrian physicist, 1887–1961) called “the finest masterpiece ever achieved along the lines of the Lord’s quantum mechanics.”[25]

The third miracle made manifest was humankind itself, which became an even more miraculous upheaval than the emergence of life. For the first time in the history of our planet, the Force that moves the worlds, the Cosmic Intelligence, hidden behind the world of phenomena, was reflected in a personal, sentient being. The Universe—both inanimate and animate—had been blindly and unconsciously following the evolutionary path until the first human beings appeared, that moment when the Universe received a soul, an intelligence, and a creative gift in humanity, opening the way for creation to rise to its highest point.

Anthropogenesis9 is a unique phenomenon: all contemporary humanity constitutes a single species. It is hardly possible to establish how this qualitative leap took place. It appears that the evolution of the psyche alone cannot fully account for the gap between the mind of the higher animal and the personal intellect of the human being. This step, as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (Jesuit priest and paleontologist, 1881–1955) correctly noted, “could only be achieved at one stroke.”[26] Of course, the development of the mental capacity of primates had to prepare the ground and conditions for this revolution. But, in and of themselves, the human spirit and the self-consciousness of an individual—things that make humans human—are miracles in the natural world.

Science can retrace evolutionary stages in the development of the brain, but it can go no further than that. The brain itself, serving only as an indispensable tool capable of detecting the subtlest vibrations of the non-material side of reality, was to become a vehicle for the soul.

Only at the moment when the light of consciousness first burst into flame in a creature that acquired human form, when that creature became a personal self, only then were the two universal realms joined, i.e., nature and spirit. “The dust of the ground,” as the Bible refers to the psychophysical nature of man, became a bearer of a “living soul” (Gen 2:7).

“So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them” (Gen 1:27). The Bible always speaks of God as Unseen Origin. Over the centuries, the topic of human God-likeness has attracted the attention of many theologians, philosophers of various schools, and scholars of the Holy Scriptures.

Although all matter carries an imprint of its intelligent origin, intelligence in nature is much like an unfinished “program”—it is faceless, “diffuse,” and dispersed. Only at the human level, this intelligence takes on the true “image and likeness” of its Creator. The universal Divine Reason, the Logos, manifesting itself in the evolution of the world, is most fully reflected through personal intelligence and conscious volition of man. The Divine is revealed to people as a Principle that transcends mechanical causality of the world, as supreme Freedom and Creativity—the two qualities that are also inherent to human nature.

God, as absolute Perfection, calls on humans to partake in the eternal perfection. This partaking goes beyond a small segment of our temporary existence: the pledge for attaining God-like perfection lies in the immortality of human personhood.

Christian anthropology discerns three levels in humans, which correspond to the threefold structure of reality and the ways of knowing it. The first level, most strongly connected to the external nature, is the body; the second, positioned at the borderline, is the soul or psyche; the third, and the deepest, is the spirit. The spirit forms the human “I” and those more exalted characteristics of human nature that reflect the “image and likeness of God.” The first two levels are common to both humans and other living organisms. But of all the creatures known to us, only humans have spirit. Body and psyche are subject to study by means of the natural sciences (the body, at any rate, entirely so); the spirit reveals itself primarily through the process of intuitive understanding and self-knowledge.

The first characteristic of the spirit is that it is realized through the self as personhood, capable of developing relationships with other persons. The Christian doctrine recognizes the infinite value of each person; it also stresses the importance of unity of individuals forming together a sublime spiritual Whole. In Christianity, this is called koinonia or sobornost, that is such a state of the Whole, in which all the parts retain their individuality and value with no detraction.

Another characteristic of the spirit is self-aware intelligence. It is this very capacity that enables us to deduce and comprehend the general laws of nature and society, cause-and-effect relationships, and the meaning of the processes occurring in the world. Conscious, rational activity distinguishes humans from nature so much so that the term “noosphere”10 is used to designate mankind.

The third characteristic of the spirit is freedom. Only humans can be the “masters of their own actions” and be held responsible for them. Animals are not free to choose—only people make choices. Moral assessment of one’s actions is a prerogative of human beings.

Of course, let us not forget that man’s willpower and his ability to rise above deterministic factors of nature are closely linked to the level of his spiritual development. A person can realize his potential for freedom only by the development, training, and cultivation of his higher spiritual abilities. Otherwise, this gift, as it were, is forfeited: being weighed down by his own base instincts and social pressures, man becomes unable to counteract them. After all, intellect, too, is a potential ability, and unless it is nurtured and trained, its capacity remains rudimentary. Children raised by animals are an example of this. Several such cases have been documented and studied. The great gift of reason in these children is like a seed thrown into the soil and left devoid of moisture and nutrients.

Thus, the formation and development of an individual are necessary conditions for revealing the person’s higher nature. One of the main traits of humanity, as indicated by our aspirations unparalleled in the animal kingdom, is in our ability to overcome purely biological boundaries. Human nature is such that the abundance of earthly blessings does not satisfy our desires or restrain our passions. We seek fullness and perfection, which biological existence alone cannot give us—neither can society or “public relations.” As people become acquainted with true freedom, they begin to develop higher and supernatural interests and yearnings. This capacity is a pledge of inexhaustible development of humanity.

The desire for freedom in humanity is so strong that even Marxists, who are inclined towards determinism, dream about a “leap from the realm of necessity into the realm of freedom.”[27] Moreover, Marx argued that this realm “lies beyond the sphere of actual material production.”[28] Despite that, he continued to view social and economic restructuring as the “basis” of freedom. While there is no doubt that the search for an optimal social system can serve the cause of true freedom, experience has repeatedly shown that without recognizing the rights of an individual and the spiritual foundations for these rights, the idea of liberation turns into its very opposite—dictatorship, violence, and slavery.

Such degradation also stems from the fact that the human need for freedom is accompanied by a fear of it. Without a focus on the Eternal, freedom can be frightening and instead give way to longing for slavery. According to Jean-Paul Sartre (French philosopher, 1905–1980), “Man is condemned to be free”[29]—a hidden terror can be sensed in these words. And yet genuine faith is unafraid of freedom: aware of all the difficulties that come along with this gift, it joyously embraces it, despite the fact that some representatives of religion have turned freedom into a cozy prison cell, thus corrupting true faith. Emmanuel Mounier (French philosopher, 1905–1950) once said, “Comfortable atheism and comfortable faith both meet in the same morass. For the one who remains faithful to the Gospel, the Apostle Paul’s precept ever lives: ‘You, brethren, have been called to freedom’ (Gal 5:13).”

The yearning for creativity, inseparable from the history of human culture, is also a realization of the spiritual dimension. Nikolai Berdyaev in his book The Meaning of the Creative Act considers creativity to be the principal distinguishing characteristic of humans which allows them to break “beyond the limits of the immanent world… towards another world.”[30]

In the creative process, a person becomes a partaker of the spiritual dimension of the world, and in this his God-like essence manifests itself with extraordinary power. That is why Michelangelo, working on his frescoes, saw his work as a divine service guided by the Spirit of God. According to Gustave Flaubert (French novelist, 1821–1880), artists are the “organs of God,”[31] by means of which He Himself reveals His Essence. Adam Mickiewicz (Polish poet, 1798–1855) in his work felt a “strength, beyond human.” Beethoven testified that in moments of musical inspirations, “God Himself spoke into his ear.” Aleksey K. Tolstoy (Russian writer, 1817–1875) dedicated a poem to the Divine nature of creative inspiration: “In vain, oh artist, you fancy yourself as the source of your works….”

The value of a genuine work of art lies primarily in the fact that its author has created a new world of its own. Colors and shapes, sounds and words become the language of the spirit.

It is no coincidence that creativity has a cosmic significance for Christianity: in it, humanity, as it were, continues the Divine act of creation. It is no longer “Earth” or “Water” with their insentient existence, but conscious beings, who create their own “second cosmos” and thereby become co-authors in the creative act of God.

That is precisely why the creative process lends itself to being perfected without limit. And that is why each master experiences dissatisfaction upon finishing his work, which spurs him on to a new creative search.

All our earthly creativity is a joy intertwined with a deep longing for perfection and the ideal. We sense great potentials within ourselves, which we are unable to fully realize: the horizon and aspirations are limitless, yet human life is but a moment of time. And this applies not only to our creative potential but also to those of freedom and intellect.

So why is there this discrepancy? Is this mismatch an unrecoverable tragedy of the spirit? If our yearning for truth, goodness, and creativity had only this fleeting nature of things for its foundation, then it would not have gripped humanity so powerfully. And since these impulses are inherent to us, they must have room for realization. Only in the perspective of an unending development of human personality, far beyond the present conditions of our existence, can this realization acquire its genuine latitude. Only then can intellect, conscience, freedom, and creativity lead human personhood to the heights of authentic God-likeness. In other words, the question of human potential is a question of human immortality.

Throughout time, people have possessed an awareness of the spirit's indestructibility, a sense as old as humanity itself. The remains from ritual burials of Stone-Age hunters speak to the early stages of belief in immortality. As a modern example, the “primitive” Bushmen, who still maintain a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, have a definite concept of immortality. According to their religion, the spirit of the deceased lives on at his grave for some time and may occasionally appear and talk with the relatives while remaining unseen. This view, for all its seeming naivety, already contains the foundations of the doctrine of immortality, which is characteristic of most world religions.

The universal prevalence of the belief that death does not entail a complete destruction of personhood is a fact deserving attention. It bears witness to the almost innate sense, albeit not always clearly conscious, of the immortality of the self. Sometimes attempts are made to link it with the instinct of self-preservation, and, of course, some kind of connection does exist. However, one’s notion of immortality is not purely a biological phenomenon. First and foremost, it is a manifestation of the spirit, which intuitively senses its own indestructible nature.

One common argument against the notion of immortality is that such a belief weakens the will and distracts one from earthly tasks. To a large extent, this critique is generated by a distortion of the very idea that it disputes. Indeed, it is no coincidence that the Old Testament and the Gospels speak so sparingly about the afterlife: a person is called to fulfill his or her calling in this world, and not just passively await a life beyond the grave. The horizon of immortality is meant to widen the perspective and make one’s labors more meaningful. Only a misconstrued doctrine of eternal life can undermine human creativity here on Earth.

Materialists often link faith in immortality with primitive scientific views of earlier eras. They assume that for people millennia ago, belief in immortality stemmed from ignorance of nature’s and society’s laws. The biological causes of death were not then known, and thus it was not possible to provide a scientific explanation of human consciousness. It remains unclear why advancing knowledge failed to utter refute the notion of immortality. It is implausible to suggest that defenders of the idea of immortality such as J.J. Thomson, the discoverer of the electron, or Erwin Schrödinger, the creator of quantum mechanics, knew the laws of nature any less than the caveman or the ancient Egyptian.

Many of the greatest minds in human history have been adherents of the doctrine of immortality and have developed philosophical foundations to support it.

The death of the body allows consciousness to transition to another form of existence. Materialists usually say that the consciousness “fades away” with death, but this is nothing more than a bad metaphor. After all, even in purely physical terms, “extinction” does not mean annihilation, but only a transition of one form of matter and energy into another.

It is quite possible to conceive of the spirit, capable of exerting an enormous influence on the life of the body, as a force which uses the central nervous system as its instrument. The brain, in this case, would be something remotely resembling a transformer or an antenna.

When the electrical circuitry of a radio receiver breaks down, it does not mean that radio waves and electrical energy have “dispersed” or “vanished.” Something similar occurs, it seems, in the relationship between the brain and the spirit. Of course, death and decay break the contact between the brain and the spirit. Yet, does it actually mean that the spirit no longer exists? Does the “silence of the graves” prove this?

The biosphere as a single organism grows, overcoming death, but its cells, being replaced, die off one after another. Immortality in the noosphere is a different matter. In the noosphere, the parts are just as important as the whole. It acts not as a faceless mass but as a unity of thinking individuals.

Death catches up with the animal seizing it as a victim; in humans, it is only the animal that dies. The human spirit, in the words of Teilhard de Chardin, “escapes and is liberated.”[32] The fact that the spirit is able to overcome the disintegration of the body is an integral part of the larger pattern of the cosmos transcending the natural and visible worlds.

But if immortality is such an important property of the spirit for evolution, if it is so desirable by humanity, then why are our ideas about the destiny of the self after death so unclear and short of detail? There can be two answers to it. According to one perspective, humanity is still destined to penetrate deeper into these secrets, which have been little explored so far but are, in principle, rationally knowable. According to the other, more likely point of view, the barrier that separates this side of existence from the afterlife is fundamentally impervious to us. As it is impossible for an embryo to understand all the complexity and multifaceted nature of human life, so it is difficult for us to envisage other worlds in our present limited mode of existence except by means of symbols. And yet, the development of the self while here, in this life, does bring it closer to the contemplation of the supersensory world. The astounding achievements of human thought can already serve as a premonition and a foretaste of immortality: they are like rays of light illuminating and guiding both the individual soul’s journey and the history of all mankind. The very essence of our spirit gives us hope for eternity despite our realization of the imminence of death. When we sense our own immortality and connection with the Universe and God, the small time period that we have here on earth is expanding into eternity. We can labor knowing that all things of this life that are true and beautiful will find their highest realization in the world to come.

It is impossible to imagine life after death as some meaningless inactivity, a monotonous and futile “wandering in the gardens of paradise.”[33] Instead, it will be a process of uninterrupted coming-into-being and ascending to eternal perfection.

“My conviction of our survival results from my view of energy,” said Goethe, “for if I work without rest to the end of my days, Nature is bound to assign me another form of existence, since this one can no longer contain my spirit… And may the Eternal One not deny us new activities, akin to those in which we have proved ourselves! If to these he should paternally add memory and an after-taste of the Right and Good that here below we have willed and achieved, we shall assuredly be but the better prepared to take our place as cogs in the cosmic mechanism.”[34]

These words of the great poet and thinker remind us that the afterlife is closely connected with the entirety of life on earth, just as someone’s birth and life are affected by heredity and the conditions of the development inside one’s mother’s body. Earthly existence is given to us neither randomly nor without a purpose. By forging our spirit on the paths of life, we prepare it for eternity. And this preparation should be expressed in our actions on earth. The philosophers of India and Greece long ago realized that, apart from physical laws, there also exist spiritual and moral laws, and that these work in a well specified sequence. Everyone takes to eternity what he has himself prepared here. A seed with a wormhole will never produce a healthy plant. Evil and spiritual insolvency on earth will be echoed in the life beyond. That is why every person here on earth is called to strive for the “salvation of one’s soul”—to become a partaker in the Divine Life. We should not view the person’s seeking the salvation of one’s soul as something selfish, rather, it is an expression of a deep drive innate to human nature, one that is diametrically opposed to selfishness. On the contrary, it is self-centeredness that becomes an impediment to the person’s partaking in the Divine Life.

Yet the Bible reveals to us something even greater. The symbol of the Tree of Life, which appears on its first pages, stands for the potential immortality of the whole human being, and with it, the entirety of nature. According to Scripture, the human being is a spiritual-corporeal unity. Therefore, our role in the Universe cannot be limited to the mere preservation and improvement of the spirit while surrounded by the general decomposition of matter. A transformed existence beyond this earthly life is therefore key to the full realization of that invisible energy embodied in the human spirit.

Through their bodies, humans are fused with the natural cosmos. The evolution of the biosphere is a flight from death; the history of humanity, on the other hand, is a journey towards resurrection and the filling of matter with spirit. Consequently, the indestructibility of the spirit is only a stage and not the pinnacle of creation’s progress. This idea was expressed by Nikolai Berdyaev with paradoxical sharpness: “Faith in an essential immortality is itself per se sterile and empty; for this type of faith there cannot be any sort of tasks to life and all the better thus it would be the sooner to die, have the soul depart the body in death, and be rid of the world. The theory of an essential immortality leads to an apologetics justifying suicide. But the great task of life becomes apparent in the instance wherein immortality should involve the result of the world salvation, if my individual fate should depend upon the fate of the world and mankind, if for my salvation there is the need to prepare for the salvation of the flesh.”[35]

Although there are obviously debatable points in these words, they rightly point to a higher human vocation than a mere egress from the material world. The cosmic task of the noosphere is to overcome the inertness of matter by the strength of the spirit, to transform and to raise matter to a higher stage of development. And the crown of the noosphere’s aspirations is the victory over physical death in nature. Humanity was created to find the path to immortality and become “the firstborn from the dead”[36] in the Universe.

But this is not what has happened. Only the spirit escapes disintegration; as before, death maintains its hold over the noosphere, breaking down the human body like any other structure.

What, then, inhibited the process and fatally impacted the spiritual life and history of the Universe? Christianity calls this catastrophe original sin or the corruption of human nature.

Though the Bible extols Man as the “master of the created order” (see Gen 1:26–28), it stops far short of idealizing him. It equally refuses to lower him to a mere animal or to deify him in a false humanistic fervor. The Bible links the apparent duality of human nature, expressed in the poetic formula: “I’m king—I’m slave—I’m worm—I’m God,”[37] with a spiritual illness that befell humanity at the dawn of its existence. It was this illness that weakened and partially paralyzed the forces originally invested into the noosphere, alienating people from God and setting them at odds with nature and themselves. The harmonious course of human development was thus disrupted, which explains much in history and the present state of humanity.

Our sad human reality now includes world wars claiming tens of millions of lives, massacres of civilians, totalitarian regimes that emerge now and then fueled by the herd instinct, unprecedented brutality, and discrimination based on social class and race. The words of Tyutchev (Russian poet, 1803–1873) come to mind: “Today it’s not the flesh—the spirit is laid bare.”[38] The nihilists of the 19th century mocked the Book of Revelation, calling it “the work of a madman.” Could they have imagined that the very epoch they were so eagerly awaiting would instead be recounted later using the imagery taken from that prophetic book?

Individuals, whether they are aware of it or not, always face a choice. Semyon Frank (Russian philosopher, 1877–1950) wrote about it as following: “Would we agree to having been created by God from the very beginning in such a way that… we would automatically without reflection and without free rational choice fulfill His commandments? And in that case would the meaning of our life be realized? But if we did the good automatically and were rational by our very nature, if all the things around us automatically and with total compulsory certainty bore witness to God, to reason and the good—then all things would at once become absolutely meaningless. For ‘meaning’ is a rational realization of life, and not the working of a wound clock; meaning is the genuine disclosure and fulfillment of the mysterious depths of our ‘I’, and our ‘I’ is inconceivable without freedom. This is because freedom and spontaneity require the possibility of our own initiative, and the latter presupposes that not everything runs smoothly and ‘automatically,’ that creative activity and spiritual power are needed to overcome obstacles. A kingdom of God which would be given ‘for free’ and which would be predetermined once and for all would by no means be a kingdom of God for us, for in the true Kingdom of God we must be free participants in the Divine glory, sons of God, as opposed to functioning not even as slaves but rather as a dead cog in some sort of necessary mechanism.”[39]

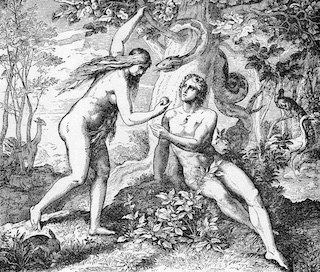

Using the freedom given to them, humanity has not only betrayed their calling but consciously opposed it. The Bible depicts this as the encroaching on the fruit of the “tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Gen 2:17) and identifies the motive for breaking the commandment as a desire to “be like gods” (Gen 3:5). This is a symbolic portrayal of human history as it has unfolded and, perhaps, above all—our own modern history. The Fall—human will opposed to that of the Creator—did not turn humans into gods. Instead, it sapped the energies that had first endowed humanity, by separating it from the Tree of Life. The law of disintegration and death overtook and subdued mankind.

The drama of primeval man is being acted out again before our very eyes in our powerlessness before sinful passions, our “will to power” that torments the human spirit, and our false self-assertion. Is not the prehistoric Fall reflected in our proud dreams of creating a world according to our own plan and design? And is not the rebellion of Ivan Karamazov—the confidence that we could have made the world better than God—nothing but a faint echo of the Rebellion that took place before the dawn of the Universe? Do we not hear in our ears the serpent’s hissing, as in the early days: “you will be like gods?”[40] A tree is known by the fruit; the father of lies by his effect on people.

The entire history of humanity has become a quest for the lost innocence, but one that requires an active use of humanity’s own powers and abilities. First there was a struggle between chaos and order, life and death, and now it is a struggle between good and evil. The doctrine of the Fall enjoins that the sin of the forefathers is an archetype of sin for all ages.

Yet, as with the birth of the cosmic order, the forces of Chaos could not stall all development, and mankind has not been fully subject to demonism and evil. The distortion of the path did not lead to an ultimate demise. A healthy root remained in Man, a thirst for perfection and knowledge, an aspiration for good, and a longing for God. Along with the partial loss of his early gifts came a promise of the further advancement of Adam’s race. The Divine Logos accomplishes His creative purpose even in this imperfect and grief-stricken world, despite the fact that our life is a “vale of tears” and the world “lies in evil” (1 Jn 5:19). Suffering and disharmony themselves elicit protest in humanity and spur people to seek ways to overcome them, and in doing so the human spirit is being forged.

Christianity does not regard suffering as something good in itself. Christ comforted those who suffered and healed the sick. Yet in the mysterious ways of Providence even evil can be transformed into good. No wonder many thinkers say that only in the “limit situations”—in the face of death, despair, or panic—is the real human revealed. The greatest triumphs of the human spirit were born in the crucible of suffering. God does not leave Man alone on this path, but strengthens him, and brightens his labor and his struggle by the light of His revelation. And eventually, the creative Logos Himself enters the world and through Incarnation unites Himself with Adam. He suffers and dies with him in order to bring humanity to the Paschal victory.

“Be of good cheer, I have overcome the world,” says Christ (Jn 16:33). “This is the victory that has overcome the world—our faith!” exclaims the Church through the lips of the Apostle John,[41] as he beheld the first fruits of the Kingdom of God.

Who could not notice the amazing change that occurs in nature with the onset of night? This change is especially felt in the summer forest.

In the daytime the air is filled with the polyphony of chirping birds; a gentle wind caresses the branches of birch trees occasionally revealing the cloudless blue sky, the sun’s glare frolics on the mossy floor, slipping through the shadows of green leaves. Glades resemble the alcoves in a quiet and majestic temple. The bright speckles of butterflies and flowers, the drone of grasshoppers, the scent of lungwort flowers—all merge into a joyful symphony of life that captivates us, filling us with peace and tranquility.

Yet the same forest looks very different at night. The trees acquire ominous and bizarre outlines, the voices of night birds resemble plaintive cries, every rustle scares and alarms us, everything is permeated with secret threat and hostility, and the pale moonlight gives this picture a nightmarish or delusional tint. Nature, so harmonious and friendly in the sunlight, as if suddenly having turned against us, is ready to strike like an ancient monster from which an enchantment spell has been lifted.

This contrast could serve as a metaphor for the change in outlook that occurred in our distant ancestors at the dawn of humanity. The gateway to the mystery of the world had been shut before them and their clairvoyance and spiritual authority over the natural domain had abandoned them. Suddenly, they found themselves alone in a vast hostile “universal forest,” doomed to a lifetime of hardship and adversity.

The solemnity and grandeur of the history of humanity’s search for lost God lies in the fact that humans have always remained unsatisfied, never quite forgetting (albeit unconsciously) the “heavenly homeland” of which they were bereft. When humans first gained self-awareness in this world, they were able to “see God face to face” (Gen 32:30). But soon after, this direct line of communication was broken. A spiritual catastrophe erected a wall between people and the Heavens. Still, humans have not altogether lost their God-likeness, retaining their ability to know God at least to some degree. The perception of the Divine Oneness was still clearly present in the early days of the primeval knowledge of God. Many primitive tribes who have preserved the way of life of their distant ancestors, too, have retained traces of an early monotheism.11

The original beholding of the One “face to face” became no longer possible following the Fall, and instead religion—restoring the link between humanity and God—began in the history of mankind. It is no coincidence that the Bible puts sacrifice at the heart of all religious behavior—the religious worship or cult. It reflects a keen albeit vague desire to atone for sin and to restore the original communion with God. By sacrificing a portion of their sustenance to the Unseen, sustenance which was earned with great difficulty, people were essentially declaring their readiness to follow the commands of the Higher Will.

Yet regaining the original harmony proved harder than losing it: gradually, God grew more distant and impersonal in the consciousness of primitive humans. Instead, they were increasingly turning their attention to the natural world.

In the mind of the primitive human there lived a sense of kinship of all living things.