History of Religion :

The Paths of Christianity

Volume 2

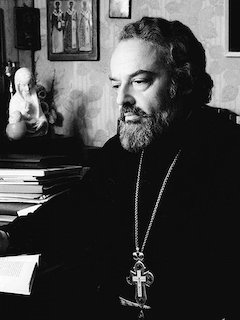

A strange sight was witnessed on the USSR Central TV on November 6, 1989: a deep-voiced, silver-haired priest of dignified appearance addressed viewers in a program called “Eternal Questions.” Such an event was unprecedented at the time, both for the Soviet audience and the state-run television alike. So much so that his ecclesiastical title—archpriest—was misspelled. What the audience could not have known at the time is that the speaker had been explicitly forbidden to use the word “God” in his 10-minute TV appearance. He spoke about a person’s inner world, the meaning of life, and eternal values. This first homily on the Soviet Central television can still be studied as a model of Christian kerygma, of how to express a man’s profound longing for higher meaning, something the priest has masterfully accomplished. The priest’s name was Fr. Alexander Men.

When religious freedom finally arrived in the Soviet Union, Fr. Alexander became a public figure, recognizable in every household throughout the USSR. Over the next two years, he delivered around 200 public lectures, speaking at Houses of Culture, universities, public schools, and even in stadiums. With his wide breadth of knowledge, he was able to get his message across to a broad audience of the Soviet people who were thirsting to hear the Good News, which had been largely out of their reach during their recent past dominated by Communist ideology. Still, the main audience in Fr. Men’s thirty years of priestly ministry was the Soviet intelligentsia—people of science, education, and culture.

On the early morning of Sunday, September 9, 1990, Fr. Alexander was on his way to Divine Liturgy when he was approached by a stranger. The stranger handed him a written note. (It is still a common practice in Russia to convey most intimate requests to a priest via a note.) Fr. Men put on his glasses, unfolded the paper and began to read. Suddenly, he was struck on his head with an axe by a second stranger from behind. Bleeding, he slowly continued on his way to church. “Who did this to you, Father Alexander?” asked a woman who came upon the bloodied priest. “No, it was no one. Just me.” He turned around and began walking back; as he reached the wicket gate of his house, he collapsed. His murder, unsolved to this day, sent shock waves across the whole country.

Alexander was born in Moscow in 1935 to secular, well-educated Jewish parents. His mother raised Alexander as an Orthodox Christian, after she had converted to Christianity and received baptism on the same day as her 6-month old son. It was the time of what became known as “the godless 5-year plan,” during which the Soviet authorities resolved to erase any mention of God. The anti-religious campaign was in full swing; even the calendar was transformed from a normal 7-day week into a 6-day week to make Sundays, along with religious holidays, fall onto work days. During that time, simply to believe was an act of bravery, and, since 1920s, a large portion of the remaining Russian Orthodox Church had gone underground in order to preserve their faith. From the early days and throughout his life, Alexander, through his mentors, stayed connected to the spiritual heritage of that part of the pre-Revolution Russian Orthodox Church best embodied by men such as the priest-saints Alexius and Sergius Mechevs and St. Nectarios of Optina. Already at the age of 12, young Alexander purposed in his heart to become a priest.

In 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, Men, who was fond of biology, began his university studies in the Moscow Fur-and-Down Institute. The Institute was transferred to the city of Irkutsk in Siberia in 1955. In 1958, when Alexander was set to graduate, he was expelled without a degree from the Institute because of his religious beliefs. The combination of Alexander’s outstanding intellect, superb social skills, and deep Christian faith was a bête noire for the Soviet system. Yet God’s hand was on the life of the future “apostle to the Soviet intelligentsia”: one month after he was expelled, Alexander was ordained a deacon; two years later, he graduated from the Leningrad Theological Seminary and was ordained a priest. In 1965, Fr. Alexander completed his studies in Moscow Theological Academy, done mostly through independent study, something he continued to pursue all his life, to his last day.

To put Men’s writings into context, we must understand what motivated him to become a voice for Christianity to his own people. The Soviet culture was categorically anti-religious, viewing any type of faith as its ideological adversary. All educational and social institutions upheld and coercively indoctrinated the materialistic creed that “science had proven that there was no God.” Materialism and atheism reigned uncontested in all quarters of society; any public mention of God, other than in a derogatory way, was considered scandalous. In the face of these universal anti-religious sentiments, there was Alexander Men, with his deep convictions, inner strength, wide erudition, and his unwavering belief in the power of Christ’s eternal message to reach his ideology-laden contemporaries.

Already as a college student, when Alexander had to take the State Examinations on political economy and Marxism-Leninism, he demonstrated his erudition and knowledge of these topics but refused to kowtow to the prevalent views or hide his Christian convictions. Needless to say, he had to suffer the consequences, but, providentially, his expulsion from the university solidified his path to priesthood and the life of ministry. During the 1960s, priests were limited to “church confines” with any activity outside the church walls strictly forbidden and all the happenings inside being closely monitored by the state security agents. The main focus of Fr. Alexander Men was to reach people with the message of Christ, for which he constantly sought new and creative ways. Fr. Alexander’s scholarship is marked by a deep understanding of the Christian message and how to convey this message to his main audience—people educated in the atheistic Soviet system. Because he could not publish in his home country, all his major writings were first published under a pseudonym abroad.

The breadth of Men’s views is sometimes confused with him being indiscriminate or insufficiently Orthodox in his convictions. However, Fr. Alexander’s living out the words of St. Paul, “I have become all these things to all, so that by all means I might save some” (1 Cor 9:22), points to the true source of his breadth. His numerous spiritual children and millions who have been reached with the profound message of Christianity remain a living legacy to his labors. Furthermore, the leading hierarchs in the Russian Church, men such as Metropolitan Anthony of Sourezh and Patriarch Kirill, highly praised Fr. Men’s works and his character as a priest.

Fr. Alexander’s own voice in his defense can be heard in his response to an anonymous critical letter by another priest. This response, given as an Appendix to Vol. 1, showcases Fr. Men’s scholarly approach to biblical studies and outlines his way of thinking by demonstrating that his approach does not constitute a novelty in the Church but, rather, extends the work of ancient Church Fathers in general and, in particular, the tradition of scholarship exhibited at the heyday of the Russian Church prior to the Bolshevik Revolution (and later continued by the Russian emigration, e.g., in St. Sergius Institute in Paris). Fr. Men’s works do not produce final answers to many of the questions being posed; he only exemplifies how to boldly engage the world with the goal of “unpacking” Christianity as a sanctifying force transforming humanity—an effort that requires prayerful and diligent work of today’s Christians. As such, Fr. Alexander Men was realizing Fr. George Florovsky’s famous thesis of “forward, to the Fathers!”

The first volume of History of Religion: In Search of the Way, the Truth, and the Life, is a condensed version of Men’s magnum opus under the same title, which consists of seven volumes. Men’s original work was more academic in nature even though it was written for the broad Soviet audience in mind. Fr. Alexander always prized a broad education and had plans to publish a more accessible version of his History of Religion. His untimely death stood in the way of his plans; this work was continued by his friends and family who condensed each of the seven volumes into the seven chapters of Volume 1.

The second volume, The Paths of Christianity, this book, provides a daring overview of the history of the Church in the first millennium, ending with the Baptism of Russia. In it, Fr. Men presents the history of the Good News spreading and taking root in medieval cultures. He does so without glossing over the more controversial aspects of Church history, adopting, so to speak, the vantage point of the Heavenly City of St. Augustine. The second volume is based on Fr. Alexander’s (incomplete) book The First Apostles (Chapter 1) and his notes on the history of the Church (Chapters 2 and 3) that he first prepared when he was still a young man, around the age of twenty. Similar to the first volume, this book acquired its final shape at the hands of Fr. Alexander’s friends who continued his work posthumously. As textbooks, both volumes are conceived to be accessible to entry-level undergraduate students.

As the translator, I felt that there was a considerable value in incorporating references to all the citations and expanding footnotes found in the original seven volumes and Men’s The First Apostles (but not available in the Russian edition of these textbooks). At times, when Fr. Alexander was paraphrasing rather than directly quoting his sources, a preference was given in this translation to quoting the original, indicating with square brackets and ellipses whenever the text was modified in some way. An index was also included to help those who want to use these books as a reference.

Since Fr. Alexander was a biblical scholar himself, who knew biblical languages and translated certain biblical passages directly from the original, none of the quotations of the Bible follow a particular English translation unless explicitly stated otherwise.

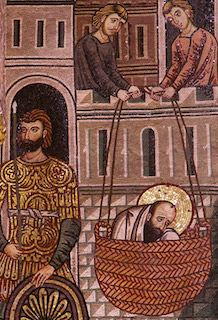

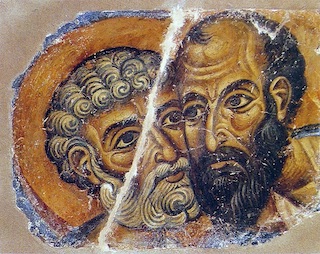

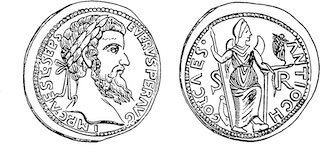

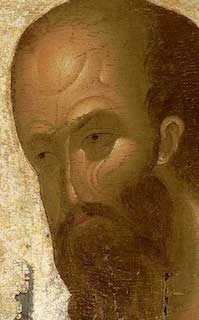

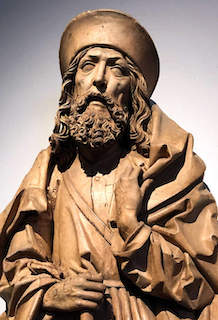

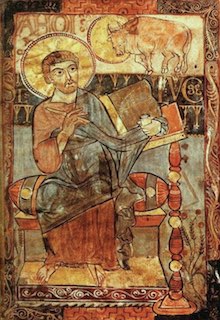

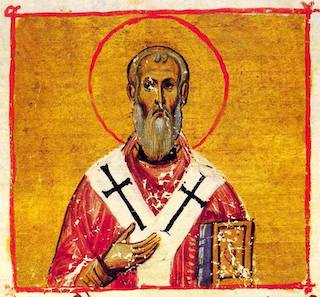

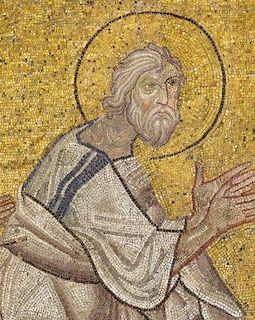

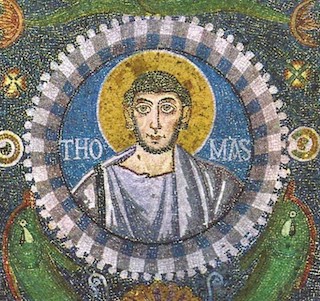

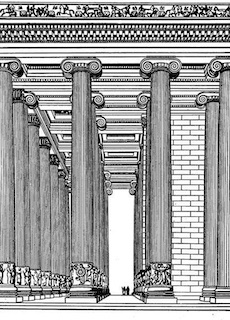

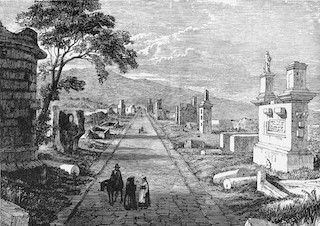

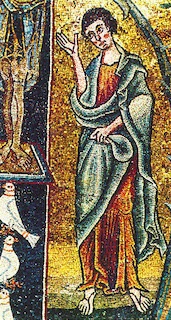

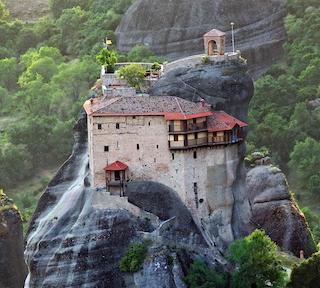

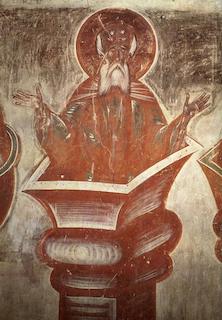

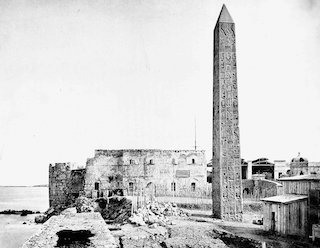

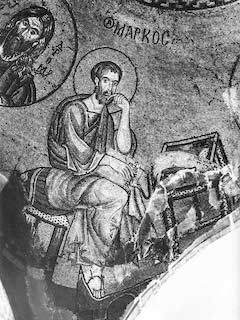

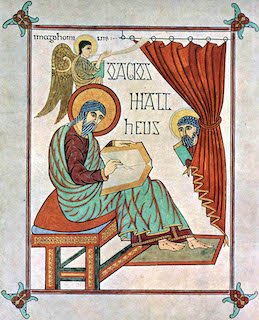

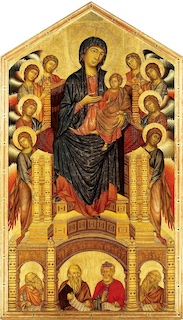

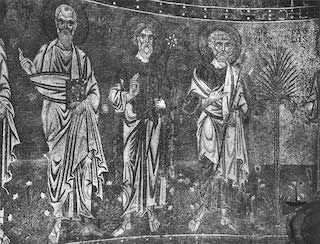

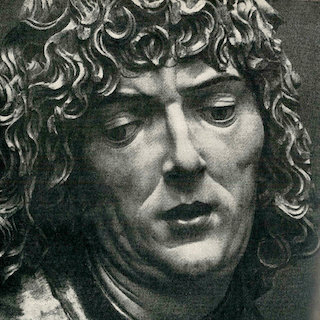

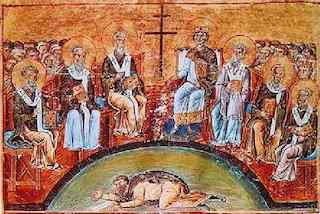

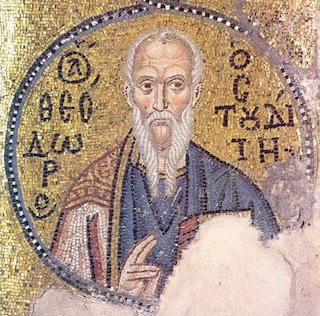

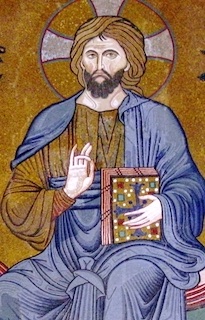

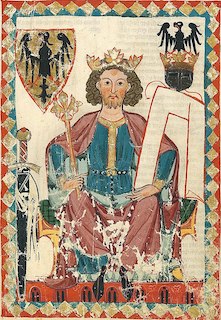

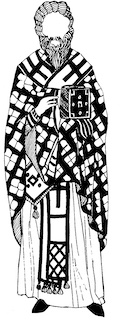

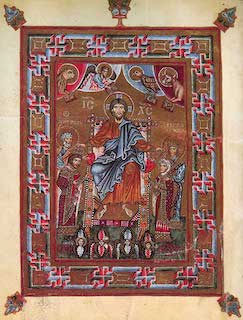

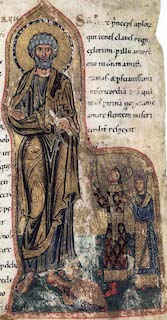

Fr. Alexander placed much importance on visuals to reach the audience with his message. Most of the illustrations found in these two volumes follow the Russian edition, but, in some cases, they have been replaced with thematically suitable alternatives. The original dating of some illustrations and artifacts has been changed to reflect the more recent sources for dating.

Like the Russian version, each of the two volumes has a section with suggested Further Reading. Whenever a suggested book was not available in English, this translation offers an alternative reading covering the same area. However, a more glaring gap exists in the reading list for the second volume, The Paths of Christianity, which, in its Russian version, includes the works of many excellent church historians of the pre-Revolution era and the first half of the 20th century (e.g., Vasily Bolotov and Anton Kartashev), experts in Eastern Church patristics (e.g., Archim. Cyprian Kern), and Soviet researchers of Byzantium (encyclopedias on Byzantine culture and writings)—the sources available only in Russian today.

On a personal note, as the translator, I have come to appreciate Fr. Men’s works in my own spiritual journey. My hope, as well as the motivation for taking on this task of translation, has been that these books will provide some wisdom and guidance in how to better navigate, reconcile, and integrate the deep spiritual heritage of humanity and of the Church with many of the challenges that face the modern world and society.

I want to acknowledge the help of many friends and family who contributed to improving this translation. Samuel Carthinhour, Waymon Lowie, and Maury Tigner spent countless hours poring over and improving my at times rugged translation. Holly Dzikovski, Matthew Andorf, and Gregory Fedorchak made many useful remarks on Volume 1. I am indebted to Hugh and Arlene Bahar for many excellent suggestions on how to improve both Volumes 1 and 2. Finally, this work would not have been possible without the continued love and support of my entire family: my wife Natalie, and sons Samuel, Alexander, and Matthew. Whenever any of the text reads fluidly, special thanks go to Natalie, whose graceful touch has enlivened not only this translation but imbues every day of my life with meaning and color.

Ivan Bazarov

May, 2021

Jerusalem, 30–35

Velleius Paterculus, a seasoned veteran and a confidant of Tiberius, was sitting in his library, finishing writing a book on the history of Rome. In that book, he examined the paths that had led the city on the seven hills—through wars and revolutions—to the position of a world power. Velleius lavished praise on Augustus and his successor for reviving “the old tradition[s]” by strengthening the rule of law and bringing glory to Rome for centuries to come.[1] The historian was convinced that the most important events in people’s lives were decided on the battlefields and in the offices of politicians. It never occurred to him, as he was writing the final lines of his book, that something new was being created far away in Jerusalem. And by whom? By a handful of tradesmen and fishermen from Lake Tiberias!

Those fishermen and tradesmen were not taken seriously even there in that strange eastern city located on the outskirts of the empire. The execution of their Master that had taken place a month prior appeared to have put an end to yet another messianic movement. The High Priest Joseph Caiaphas remained unruffled in the face of incredulous rumors that were circulating throughout Jerusalem at the time: what else to expect from the superstitious crowd. Pontius Pilate returned to Caesarea immediately after Passover and immersed himself in work; he had enough worries and concerns on his hands, and the incident with the “King of the Jews” quickly faded from his memory.

Meanwhile, the quarter in the eastern part of the city where Peter and the disciples settled with their friends, relatives, and new members of this religious community, had its own special existence. They lived as a big family with “one heart and soul” (Acts 4:32).

According to the Book of Acts, about one hundred and twenty Galileans arrived in Jerusalem. It is possible that their number was even larger, but traditionally 120 was considered a minimum for creating a separate community.[2] In Palestine and beyond, there were many such brotherhoods, or Haburot (associations), gathering together for prayer meals. The ecclesiastical and civil authorities were largely tolerant of them.

Those communities varied in their degree of isolation; some of them, such as those who lived near the Dead Sea, all but completely severed their connection with the rest of the world. The community of Christ’s disciples, who became known as the Nazarenes,1 was, however, different. That small group of devout did not intend to stay cloistered and isolate themselves either from the Temple or the faith of their fathers.

It was not because of inertia that they kept their attachment to the faith of their fathers. A departure from the Old Testament for Jesus’ disciples would amount to a departure from the Lord Himself who had lived and taught building on the foundation of the divinely revealed faith. His own coming was in fulfillment of biblical promises. The apostles were hoping that the New Covenant that He had established would quickly spread to all the people of God; although it did not happen, the Church continued to maintain a strong connection with the heritage of Israel through Tradition and the Bible.

Whereas men prayed separately from women in synagogues, and the rabbis did not allow women into their schools, the apostles did not want to disregard the will of their Master, who had been always surrounded by men and women alike as His disciples. Thus, the faithful prayed together in homes as if anticipating Paul’s words: “There is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28).

Miriam, the Mother of the Lord, whose care was entrusted to John Zebedee, was surrounded by veneration, although she still humbly kept in the background. This explains the duality of Her image in the New Testament. On the one hand, She was the chosen one of God, “the blessed among women,” but, on the other hand, the Keeper of the Mystery, known only to a few followers. It was as if She Herself intentionally shun any fame or glory. The impression left by Her Person was, however, undoubtedly enormous. This explains the legends that surrounded the name of Mary already among the first generations of Christians.2

As in the days of Passover, both bitter and joyful, Her sister Salome, the wife of Zebedee, Mary Magdalene, and other Galilean women were inseparable from Her. They all went to Jerusalem with the apostles. Yet from that moment on, their traces are lost. Perhaps, these women, who treasured the memories of the Gospel events in their hearts, continued their humble service in the community, and some of them even returned to Galilee. Who were those who listened to their stories about the Teacher? Who was warmed by the fire of their faith? This we have no knowledge of. The work of God is often accomplished in mysterious ways and through inconspicuous people.

The Lord spoke of the calling of the Twelve, who, upon the advent of the Kingdom of God, would play the role of patriarchs and founders of true Israel, the Church of the New Testament. The biblical number was, however, broken because one of them fell away. Judas sided with the enemies of Jesus and then disappeared. Although his death was known about, there existed different accounts of it.3

To fill in the vacancy, Peter announced at one of the meetings the need to find another man in place of Judas. Convinced that the traitor’s end was foretold in Scripture, the apostle proposed replacing him with a disciple who had been with Jesus from the first days and saw the Risen One. Oddly enough, there were only two individuals who met the criteria: Joseph Barsabbas and Matthias. All the other possible candidates apparently remained in Galilee.

To decide between the two, they resorted to the Old Testament custom of casting lots and praying that God Himself would choose the worthier one. The lot fell to Matthias, and he was “numbered” with the Twelve.4 By this act, the apostles bore witness to their faith in the promise of Christ.[6]

Summer was coming in Judea. The grapes were not yet ripe, but the fields around Jerusalem had already turned yellow. The period of shavuot, or the weeks, leading up to the Feast of Pentecost, was drawing to a close. That year it fell on May 29th.

The celebration had long been timed to coincide with the beginning of the wheat harvest. During that time, the priests replaced the old bread before the altar in the Temple with showbread baked from the grain of the new harvest. But in addition to the wheat harvest, the feast of Shavuot commemorated the giving of the Law. The rabbis used to say that God’s voice at Sinai sounded in seventy different languages according to the number of the nations on earth.[7] In an apparent confirmation of this legend, Jerusalem turned truly multilingual during the holiday. It brought together representatives of “all Israel” from many parts of the world, as well as proselytes5 of various nationalities. Some pilgrims had not left Jerusalem since the days of Passover.

The Nazarenes were also filled with a festive anticipation. With great joy and hope, they were full of confidence that God had ordained them to be His witnesses. On the night of Pentecost, which was set aside for reading the Torah, the Lord’s disciples were looking for places in Scriptures that pointed to Christ. Every event in His life, His death, and Resurrection took on a new perspective in the light of the prophecies. They may have had access to small collections of Messianic texts: such scrolls already existed at that time, particularly among the Essenes.

With the onset of the festive night, the apostles were reading and praying in the upper room of their main meeting place. This house apparently belonged to Mary the Jerusalemite, the mother of John Mark (who later became a companion of Peter and Paul).

At the approach of the dawn, everybody present was overtaken by something utterly unexpected. They felt as if the fire of Heaven had pierced them, resembling the experience of the Old Testament prophets at the time of their calling. There were no words to describe such an unparalleled experience other than using symbolic imagery. Accordingly, the Evangelist Luke6 uses biblical symbols of epiphany when referring to the descent of the Holy Spirit: “a sound from heaven, as of a rushing mighty wind,” and “dividing tongues, as of fire” (Acts 2:2–3).

Outside observers could only see how a crowd of Galileans, easily recognizable by their guttural dialect, left the house and loudly praising God proceeded to the Temple. Standing among the columns of Solomon’s porch,7 they continued to pray and sing in the Temple.

The group of Galileans was drawing attention to themselves even though loud displays of emotion were common in the East. Their enthusiastic praising was not bound by their language, as they seemed to be speaking in an unknown dialect. What was absolutely incredible is that their ecstatic babble was intelligible to those whose hearts were open. They understood it despite the fact that many of them who lived far from Judea had long forgotten their native language, while others did not even know it. However, as is often the case, the miracle remained incomprehensible to skeptics and unbelievers. They were scoffing Galileans explaining away their ecstasy by wine.

What does it mean to “speak in other tongues?” It is hardly possible to establish in detail what happened on the morning of Pentecost in 30 AD. St. Luke related a story of the event that had taken place half a century before he wrote his book. It is unlikely that the apostles received a permanent ability to speak foreign languages. Most likely, the Evangelist described a case of glossolalia, which refers to speech-like utterances in an ecstatic state. Glossolalia could explain why outsiders hearing the apostles thought they were drunk. The Apostle Paul, too, said that people speaking in “unknown tongues” may appear like madmen to outsiders who walk into a congregation (see 1 Cor 14:23). But this would be merely an outsider’s impression. Importantly, people who did not speak Aramaic were able to understand the apostles’ unusual praises. The message went from heart to heart, bypassing language barriers. This event could be seen as a foretaste of the universal spirit of the Gospel that transcends any country or tribe boundaries.8

Then why did Luke describe the events of Pentecost as unique? He must have been well aware of glossolalia often accompanying believers’ prayers when overshadowed by the Spirit in Christian communities, implying that the miracle was not in “speaking in tongues” per se. In early churches, the Spirit descended only through the laying on of the apostles’ hands. But the unique thing about the events of Pentecost was that the power of God operated without any intermediaries. The miracle was in the complete rebirth of the disciples: fearful and indecisive only a day before, they suddenly became courageous heralds for the Messiah.

A special outpouring of the Spirit was needed to give momentum, vitality, and insurmountable power to the nascent Church. Without such empowerment, the rapid spreading of the streams of the new faith would have been impossible. In only two or three decades, the Good News spread from Asia to Gibraltar—this was the tangible and indisputable result of the outpouring of the Spirit. And one more thing: the real witnessing began only when the “unknown tongues” fell silent.

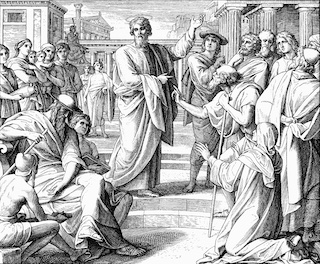

Peter rose to the platform and the crowd immediately fell silent. The dozens of wondering, anxious, and questioning eyes were peering at him all around. While the fisherman had made proclamations at the command of the Teacher before, this time he was not in a Galilean village but in the spiritual center of Israel. He was addressing the crowds who had come from distant great cities; famous scholars may have been found among them. However, he was not the same Simon either. At first, he appeared small against the backdrop of huge buildings and the multitudes. As he continued, he seemed to have grown bigger with his voice thundering imperiously under the arches of the portico as if an experienced tribune was addressing the crowd. It was as though an ancient prophet suddenly appeared in Jerusalem.

“Men of Israel!” solemnly proclaimed the Apostle. “Jesus of Nazareth, a Man attested by God to you by miracles, wonders, and signs which God did through Him in your midst, as you yourselves also know—Him, being delivered by the determined purpose and foreknowledge of God, you have taken by lawless hands, have crucified, and put to death. Him God raised up, having loosed the pains of death, because it was not possible that He should be held by it” (Acts 2:22–24).

Peter again made a reference to Scripture and came to a shocking conclusion: “Therefore, let all the house of Israel know with certainty that God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Christ” (Acts 2:36).

The apostle stopped and silence spread over the crowd. If this man’s words were true, then something catastrophic had undeniably happened. It was unlikely that those standing in the crowd had ever seen the Nazarene, although it is possible that some of them might have been in the city during Passover. The execution of the Galilean Teacher had gone past them, leaving them indifferent, but upon hearing Peter’s words, they accepted them wholeheartedly. They were captivated not by theological arguments but by the power emanating from this man who resembled Amos and Isaiah. It became clear that God Himself was speaking through him.

“What shall we do? What shall we do, men and brethren?” a chorus of discordant voices was heard all around.

“Repent, and let every one of you be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. For the promise is to you and to your children, and to all who are afar off, as many as the Lord our God will call” (Acts 2:38–39).

These words did not surprise anyone, for ablution had long become an accepted sign of spiritual cleansing—one that opened the way to a new life—practiced by many teachers, including John the Baptist.

The ensuing events transpired very quickly. The crowds led by Peter descended to the stone arcade where the stream formed the Siloam reservoir. The reservoir was partitioned into two sections: for males and females. The apostles were baptizing everyone who repented with pilgrims waiting in long lines for their turn. Some of them were baptized in the Temple pool—a mikveh—used for ceremonial immersion. By evening’s time, the number of converts had already reached three thousand.

The worshipers did not want to disperse. Instead they were intent on staying together: day after day, they eagerly listened to Simon Peter and other apostles. They learned from them that the Kingdom of God had already come and that the Savior brought reconciliation with God. They also heard that the Messiah expected them to be pure of heart and compassionate to one another and that He would soon appear to judge the living and the dead.

Caiaphas was most certainly informed about the incident; he may have even witnessed some of it himself. But the time was not right to take drastic measures because of the holiday, which brought many pilgrims to the city. Therefore, the members of the Sanhedrin decided to wait, hoping that the restless Galileans and their agitated supporters would soon leave the capital, and the wave of enthusiasm would die down on its own.

Their hopes, however, turned out to be false.

Christ once said to His disciples that if they had faith, they would do greater signs than He Himself had done (see Jn 14:12). The power of the Spirit manifested not only in the power of the apostles’ words, but also through their actions. Although even the disciples themselves were not initially aware of it. The miracles began when Peter and John came across a crippled beggar at the gates of the Temple who was asking them for alms. Obeying the Master’s command to help the afflicted, Simon boldly said: “Silver and gold I do not have, but what I do have I give you: in the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, rise up and walk.” With these words, he raised the beggar by his hand. “And immediately,” writes Luke, “his feet and ankles received strength. So he, leaping up, stood and walked and entered the Temple with them—walking, leaping, and praising God” (Acts 3:6–8). The healed man stayed with Peter and John in Solomon’s porch, which was quickly flooded with people filled with horror and delight at the miraculous healing performed by the apostles.

Again, thousands were baptized.

Not surprisingly, the apostle’s miracle caused a greater commotion than his preaching. Luke writes, “they brought the sick out into the streets and laid them on beds and couches, that at least the shadow of Peter passing by might fall on some of them” (see Acts 5:15). This is when the authorities realized and became increasingly concerned that the story of the Nazarene lived on and they could no longer delay an intervention.

The supreme tribunal, the Sanhedrin, was in the hands of the Sadducee party, representatives of the higher clergy and highborn chieftains. They looked with suspicion at all religious innovations, including the belief in the coming resurrection of the dead. The Sadducees got along well with the Roman administration while striving to suppress the rebellious mood among their own people. They were the ones who condemned Jesus and handed Him over to the procurator. Seeing that the disciples of the Crucified One were beginning to stir up trouble, the high priest ordered the arrest of Peter and John.

Caiaphas was surprised by the bold answers of the Galileans who were “uneducated and common men” (Acts 4:13). “Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you more than to God, you judge. For we cannot but speak the things which we have seen and heard,” (Acts 4:19–20), they said to the high priest. Although the feast passed and pilgrims were beginning to leave the city, Caiaphas still feared potential unrest and released the apostles after issuing them threats. However, he soon regretted and reversed his decision by ordering their second arrest.

Luke writes that an “angel of the Lord” freed Peter and John from prison and they voluntarily went back to the Sanhedrin to appear before the elders. It remains unknown whether it was literally a miraculous release or someone, risking a severe punishment, secretly organized their escape9 (Acts 5:19–20).

Caiaphas accused them of instigating unrest and insurrection: “You have filled Jerusalem with your doctrine, and intend to bring this Man’s blood on us!” This reference to Jesus by avoiding calling Him by name would become common among those in Judea who opposed Him and His followers (Acts 5:28). The Sanhedrin was wary that the speeches and the healing by the Nazarenes could reignite the memory of Jesus’ execution, which was beginning to fade away, and the crowd’s indignation against the legitimate authorities. But things have changed, and Peter stood firm, instead of hiding and trembling at the gates of Caiaphas’ house: “We ought to obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). The Sadducees were furious.

The help came from an unexpected direction. The party of the Pharisees in the person of their leader Rabban Gamaliel stood up in defense of the Nazarenes. It was later said of the Rabban that with his death, the glory of the Law ceased, and purity with abstinence disappeared.[8] The Pharisees, contrary to popular belief, were not uniformly sworn enemies of Christ. There were many of His secret and open followers among them. Furthermore, their old feud with the Sadducees only reinforced Gamaliel’s desire to free Peter and John. He declared that the truth of the new teaching could only be judged by God. More than once, there had been sectarians and deceivers who pretended to be messengers of heaven, but they all were quickly forgotten. “And now I say to you,” said the Rabban, “keep away from these men and let them alone; for if this plan or this work is of men, it will come to nothing; but if it is of God, you cannot overthrow it—lest you even be found to fight against God” (Acts 5:38–39). The words of the wise Pharisee had an impact, especially since Caiaphas realized that Pilate would be reluctant to side with the Sadducees again and authorize new reprisals.

Peter and John were punished with thirty-nine lashes; according to the Law, this number signified that the case was settled and that the person was cleared of guilt.[9] The cruel scourging did not crush the apostles; they went to the brethren, “rejoicing,” as Luke writes, “that they were counted worthy to suffer shame for the name [of Lord Jesus]” (Acts 5:41). The Sanhedrin positioned itself for further developments.

The opposition from the authorities was not the greatest challenge faced by the Church. The most pressing issue was how to organize and direct the lives of the converts who already numbered in several thousands. The majority of the Galileans and those who joined them had neither a permanent shelter nor income to support themselves in Jerusalem. The apostles did not want to leave the city because the Lord Himself commanded them to stay there for twelve years.10 Moreover, they could not abandon the newly baptized who were in need of the instruction, support, and care.

The disciples were not distinguished by any special experience or talent. Everything they were able to accomplish was performed by miracle, through the power of the Spirit.

One of such miracles was love among the believers. Believers were not simply “like-minded” individuals, but true brothers and sisters, united by strong cordial bonds. They were all willing to share their possessions—up to the last coin—with one another. The richer among them were selling their property or land and bringing the proceeds to the apostles as a contribution to the common treasury. Others shared their houses and fed the poorest among them. While people of means were in the minority, the community was materially sustained thanks to them. Among those who did much of the community were Mary, Mark’s mother, whom Peter lovingly called “his mother,” and her relative Joseph Barnabas, a Levite who had come from the island of Cyprus. He was a noble person called “the son of consolation,” Paul’s future friend and companion. He became a source of information to Luke who learned from him the stories about the early years of the Church in Jerusalem.

One of them is a sad recounting of the story of Ananias and Sapphira, showing that the community did not consist of ideal people. These two, wishing to be known as benefactors of the Church, brought Peter the money from the sale of their estate. By their account, they had given away everything they owned. In reality, the couple concealed some of their proceeds. Instead of the due recognition he was expecting to receive, Ananias was sternly rebuked by Peter who read the deceiver’s true intent. According to Church tradition, both Ananias and his wife, who followed in her husband’s steps, suddenly fell dead11 (see Acts 5:1–11). The apostle Peter’s indignation at their deception was not a spontaneous outburst of anger. According to Luke’s narration of the event, Peter’s pronouncement of the judgment that they “lied to the Holy Spirit” who lived in them revealed the pain of betrayal experienced by the body of believers.

The apostle’s reproach to them is equally noteworthy: “What was acquired by selling, was it not in your control?” (Acts 5:4). These words reveal a voluntary nature of believers’ sacrifices to the apostles and that there was no strict charter in the Church, unlike that of Qumran that required a renunciation of all property. What the Jerusalem community valued was brotherly love, as expressed by believers freely and voluntary.

It was a common practice for believers to gather in their houses at night time: they solemnly broke Bread as on Passover, gave a Eucharistic12 prayer of thanksgiving, a reminder of the passion of Christ, and passed the Cup from hand to hand.

Jerusalem – Damascus, 35–37

There were several converts from the diaspora countries who got baptized on the day of Pentecost. At that time, the majority of the people of Israel already lived in Diaspora. By most optimistic estimates, out of the seven to nine million Jews who inhabited the Roman Empire, only one and a half to two million lived in Palestine.[11,12]

In Antiquity, two peoples—Greeks and Jews—were destined to live in large diasporas. The modest lots of their poor homelands became too narrow for them. The Greeks could be found from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Jews also settled throughout the Mediterranean region and further to the East, as far as Parthia. The places of diaspora settlements usually coincided with the caravan routes. Living alongside the Greeks, the Jews embraced many elements of their civilization, and those among them with a Greek mother tongue became called Hellenists. They kept their biblical faith and made an effort to visit the Temple at least once a year; some of them, having traveled to Jerusalem, chose to stay in the homeland of their ancestors for good.

However, the poor knowledge by Hellenists of their ancestral tongue prevented them from merging with the locals; they were often treated with arrogance, if not with contempt, so they preferred to settle in special quarters of the city and establish their own synagogues. Among the several hundred prayer houses in the capital, a considerable number belonged to those who came from Egypt (Alexandria and Cyrene), Antioch, and Asia Minor. A separate group was comprised of the “Libertines,” the descendants of Roman freedmen.

These people read Scripture only in the Greek translation and followed the customs learned in foreign countries. The most educated of them applied themselves to philosophy and literature that arose at the fusion of Judaism with Hellenism.

The entry of the Hellenists into the Church marked an important milestone. Despite creating many difficulties, it broadened the intellectual horizon of the Church and introduced new trends into it.

The main challenge was that people from the diaspora lived in a certain isolation; language and cultural barriers set them apart from the Hebrews—the Aramaic native speakers. And this could not but affect their standing among the Nazarenes.

It is generally believed that Luke gave an idealized picture of the life of the first community of believers, but in reality, he did not hide its dark sides, as can be seen from the episode with Ananias and Sapphira. Nor was he silent about the tensions that arose between the groups of Hebrews and Hellenists. We do not know the exact nature of those tensions. The Evangelist only points out that as a result of those tensions, Greek-speaking Christians began to complain about their brethren. They claimed that their poor, especially widows, were being neglected in the daily distribution of bread.

Whether this was indeed the case or the reproaches stemmed from the suspicion by the Hellenists, the apostles realized an imminent need to solve the problems, which emerged in the community. Otherwise, they would have to carry the responsibility to attend to the everyday community needs themselves, “having left the word of God.” Therefore, the apostles decided to follow the path of the division of labor: having conferred with other elders, they proposed to create a council of “seven men” of good reputation,13 wise, and filled with the Spirit, and entrust them with the task of organizing daily sustenance.

The proposal was immediately accepted. It was quite consistent with the Jewish tradition of appointing a collegium of “seven virtuous men” to head urban communities. Following that model, the apostles chose the Seven14 for the ministry: Stephen, Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas, and Nicholas. To fend off any future conflict, all seven candidates came from Hellenists.

As it was typical with the appointment of the members of the Jewish Council, hands were laid on them15 with a prayer that the Spirit of God would assist them in their work. This meant that it was not simply an administrative position, but rather an office of ministry. Apparently, each of the seven men ordained for “serving the tables” celebrated the Eucharist as the head of the congregation. The apostles themselves could hardly keep up with everything, considering that the number of the faithful by that time had reached eight thousand.

Thus, the problem seemed to have been resolved with no apparent obstacles standing any longer in the way of the Church. People were treating the Nazarenes—pious, kind, and zealous in the Law—with love and respect. The authorities were no longer acting hostile toward them. The followers of Christ were tacitly recognized as an independent community. Nothing seemed to forebode new trials. The Church did face a difficult prospect of spreading the Gospel to the Gentiles, but the Nazarenes were in no haste to do so because there was still plenty of harvest at home.

Some Church historians argue that Christ never intended a global mission for His disciples. Indeed, in the beginning, He said that the apostles should not preach among the Samaritans and Gentiles, but He also predicted that people would come to the Kingdom of God from east and west (see Mt 8:11). If we ignore these words and the command given by the Risen One “to go and make disciples of all the nations” (Mt 28:19), it becomes unfathomable how Christians came up with the idea of a global mission. It so happened that the mission itself was precipitated by an unexpected crisis caused by Stephen’s preaching.

St. Stephen stood out among the Seven, most likely serving as their head. All of them were devoted not only to practical affairs, charity, and Eucharistic meals, but also to proclaiming the word of Christ. In Acts, Philip is even called an evangelist. Stephen, evidently, proved to be the most dynamic of them. In addition to fulfilling the ancient commandment of Scripture and the precept of the Church—to care for the poor—he was also active as an evangelist.

Christ’s teachings did not abolish the Law and rituals but singled out trust and love as their essence. Christ Himself called the Temple a house of prayer, although He did not regard the Temple buildings and the magnificent sanctuary decorations as something foundational. Buildings can be destroyed; only spirit and truth are indestructible. He Himself built the Church in three days, giving her new life by His resurrection.

This message of Christ about the secondary role of external forms of worship was also at the center of St. Stephen’s preaching. Only fluent in Greek, he most often addressed his fellow countrymen, the Hellenists, in synagogues. Many of them were sympathetic to his ideas, as their ancestors were able to preserve and deepen their faith despite the distance separating them from the Temple.

However, not everyone among the repatriates was like that. Having resettled to Palestine, some became even more zealous in their piety than the most extreme orthodox native to the Land. Stephen’s words cut them to the quick, causing most heated arguments and even a rift in the Greek-speaking synagogues. The more persuasive Stephen’s arguments based on the prophets were, the more anger and opposition they caused among his opponents. In the end, his opponents—the traditionalists—prevailed and they even managed to stab Stephen in the back. Their informers came to the Sanhedrin and accused Stephen of insulting the sanctity of the Temple and blaspheming the Law.

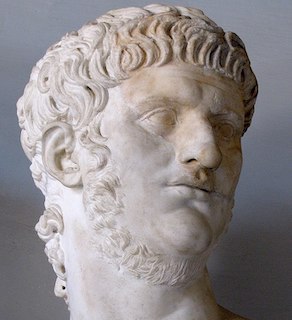

Around that time, an unrest broke out in Jerusalem. Pilate’s cruelty exceeded all limits, and the situation in the country reached a breaking point. A delegation of locals was hastily dispatched to the governor of Syria, Vitellius, with a demand to remove the procurator from Judaea. Vitellius realized that the matter had taken a dangerous turn, and ordered Pilate to appear before the court in Rome, temporarily replacing him with a certain Marcellus.16

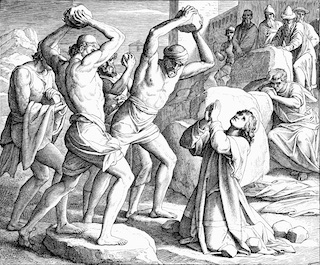

It was during that brief moment of anarchy, which had spurred rampant fanaticism, that the agitated crowd incited by the Hellenists seized Stephen and brought him before Caiaphas. “This man,” shouted the accusers, “does not cease to speak blasphemous words against this holy place and the Law… We have heard him say that this Jesus of Nazareth will destroy this place and change the customs which Moses delivered to us” (Acts 6:13–14).

Stephen was asked if he would plead guilty, but he categorically rejected the slander. As he stood before the judges, he felt a surge of supernatural inspiration, and his face resembled the fearsome face of an angel (see Acts 6:15). He began his defense from afar.17 His goal was to show that the entire history of God’s people paved way for Jesus’ coming, and that His death was far from being a tragic coincidence. He recalled the Covenant with Abraham, the deliverance from Egypt, the Law given through Moses, the Promised Land, and the construction of the Temple. Concurrently, he emphasized how often God’s people had opposed His will. He further spoke of the brothers who had sold Joseph into slavery, the Israelites who had rebelled against Moses, the golden calf, and the temptations of idolatry. God had a great purpose, which went far beyond the construction of the Temple.

Stephen’s gaze rose above the angry crowd to witness a divine vision flashing before him. “Behold,” he exclaimed, “I see the heavens opened, and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God” (Acts 7:56).

Upon hearing those words, the crowd roared with rage. The fanatics covered their ears to block out his words. The trial stopped in its tracks. The building was quickly overrun by the crowd: no one was paying any attention to Caiaphas. Although he was in the position to interfere by calling the guards, he caved in to the crowd and turned the Hellenist over for lynching.

Stephen was hauled out of the hall and dragged to the gates of the city with the crowd screaming in a frenzy (someone remembered the old custom of carrying out capital punishments outside the city walls). This is where the bloody execution took place: he was thrown off the cliff, and the accusers finished him off by stoning. Meanwhile, Stephen was praying for his murderers.

The instigators, however, did not want to stop at one victim. They launched a manhunt for Stephen’s supporters in the city. Apparently, they were mainly looking for Hellenists, and did not spare even women. The apostles were left alone for the time being; the Galileans’ respect for the Temple was too obvious to accuse them of sacrilege.

St. Luke writes that in those days all the faithful fled the city (see Acts 8:1). Yet it appears that most took refuge in Bethany and other nearby villages only soon to return to the city. The Hellenists, previously led by the Seven, were the ones who left Jerusalem for good. Some went to the cities in the north and along the seacoast; others left Judea to return to their native lands, in particular, Antioch.

Thus, the death of St. Stephen served as an unexpected impetus for further expansion of the Church. There was another aftermath of this tragedy. As St. Augustine put it, in response to the first martyr’s prayer, the Church received the Apostle Paul.

As the murderers were executing St. Stephen, they laid their garments at the feet of a young Pharisee, Saul of Tarsus. He did not take part in the execution; yet, having volunteered to guard the clothes, he expressed his solidarity with them. Convinced of the justice of the punishment, Saul, although not cruel by nature, was adamant. The Pharisee, having conquered any doubts that may have crept into his soul, joined the manhunt for the Hellenistic Nazarenes.

Like Stephen, Saul18 was not a native of Judea. He grew up in the diaspora, in the Cilician capital city of Tarsus, where East and West met; philosophy, sports, and trade flourished. Saul’s family had a hereditary Roman citizenship, as evidenced by the Tarsian’s other name—Paul, which was of Latin origin. However, he was proud that he had not become a Hellenist, but was “a Hebrew of the Hebrews”:[18] he preserved his paternal language and kept to the traditions of his ancestors.

And now he was standing at the edge of the cliff, looking down with a heavy feeling at the motionless, blood-covered body of Stephen. It was all over. Or was it?

Soon Saul learned that some devout Jews managed to take away the body and bury it with honors, even though mourning was not in order for those whose bodies were stoned.[19] It could only be explained by the fact that there were many supporters of Stephen. They had to be crushed immediately to capitalize on the anger of the townspeople, before the new procurator would arrive.

Saul knew that the respected Gamaliel was opposed to violence, yet Rabban, too, could be mistaken in not taking the threat seriously enough. The young Pharisee thought that new rioting could be avoided if the apostates were given a fair trial. The Council and Caiaphas would support such measures for they cared deeply about upholding the Temple’s authority.

At the meeting of the elders, Saul sided with the members of the Sadducee party, although they were hostile to him as a Pharisee, and was eventually appointed to be in charge of the persecution. Many Nazarenes were thrown into jail; while awaiting trial, they were being forced to deny and curse the name of Jesus. Yet Saul craved even more retribution. Having begun to act in concert with the Sadducees, he was determined to go all the way. He was informed that the heretical contagion was spreading out, and that Damascus had become one of its centers, with the sect of the Nazarenes taking root in that populous Jewish colony.

Saul knew he had no time to waste. He came to Caiaphas and asked for a mandate: he planned to find the sectarians in Damascus and bring them to Jerusalem in custody. While Caiaphas was mainly concerned with the events in the capital, he liked the indomitable fervor of the young scribe. Paul’s zeal gave him hope of stifling the unrest before the arrival of the procurator. The high priest readily gave Saul letters to the heads of the Damascus synagogues and appointed him as his shaluach—an emissary or a messenger.

Fate moves in mysterious ways: in a week, this shaluach-inquisitor would turn into a different kind of messenger—the apostle of Jesus Christ.

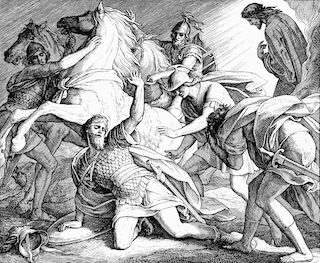

Shortly before Passover, Saul, accompanied by Caiaphas’ men, left the city gates. The Pharisee, invigorated by his mission, set out on a long journey as a defender and servant of the Law of God. He was driven by his ostensibly righteous anger, which may have concealed his inner turmoil. His main enemy was no longer the defeated Stephen or other apostates from Hellenists, but as Caiaphas, he was seeking to eradicate from the national memory the very name of the crucified one, Yeshua Ha-Notzri, the alleged messiah.

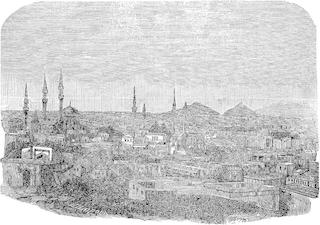

They had to travel at night along the rugged Syrian roads to avoid heat exhaustion. Moving forward in the darkness, Saul was immersed in agonizing thoughts. He could not shake them off, and yet he remained firm, with no visible sign of hesitation. They had been traveling for over a week. Damascus was already in sight. Vineyards, fields, and orchards spread across the vast plain surrounding the city. Saul and his companions no longer made stops to rest. They moved hastily, ignoring the midday heat. The Pharisee was pondering how to begin his conversation with the elders, to convince them of the need for drastic measures, and then to take the guilty back to Jerusalem.

Suddenly the tense silence was struck by an incomprehensible sound, a flash of light that momentarily eclipsed the sun.

When people came to their senses, they saw their leader Saul lying motionless in the middle of the road. They rushed to him, picked him up; he was fumbling around like a blind man. They had to lead the Tarsian by the arm. This was not the manner in which they expected to enter Damascus. They had been led by an ardent zealot and a judge who was suddenly reduced to a helpless, withdrawn, and blinded man.

The whole group was dumbfounded at what had happened and had no explanation for it.

Years later, as if answering this very question, Paul wrote: “He, who had separated me from my mother’s womb and called me through His grace, was pleased to reveal His Son in me” (Gal 1:15–16).

The Evangelist Luke probably heard from the apostle more than once the story about his encounter on the outskirts of Damascus. The Lord Himself overtook him and set him on a new path. “He heard a voice,” writes Luke, “saying to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting Me?’ And he said, ‘Who are You, Lord?’ Then the Lord said, ‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting’” (Acts 9:4–6).

In Damascus, Saul asked his companions to take him to Straight Street to see a certain Judas. Still bewildered, the escorts, nevertheless, obeyed him. In a state of near shock, the Tarsian stayed with Judas for three days without eating. He was surrounded by complete darkness.

On the third day, he was found by a respected Jew in the city named Ananias. We do not know when and where he became a Christian, only that Ananias had already learned from hearsay the name of the persecutor. Not daring to disobey the command of God, he went to see the notorious persecutor. Ananias entered the house of Judas, inquired about Saul, and when they brought him to the blind Pharisee, he exclaimed: “Brother Saul, the Lord Jesus, who appeared to you on the road as you came, has sent me that you may receive your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit!”

“And it was,” writes Luke, “as if scales immediately fell from his eyes” (Acts 9:17–18).

That same day, the Tarsian was baptized in the name of Jesus. Then, according to Acts, Paul openly declared himself to be a confessor of the newfound faith. But in the Epistle to the Galatians, the apostle himself makes a clarification. According to his report, shortly after his conversion, he withdrew to Arabia, at the neighboring Nabataean Kingdom (see Gal 1:17).

Apparently, he was unable to immediately face those who had been waiting for him as a stern guardian of orthodoxy. Paul’s soul required solitude. He needed to come to his senses and to process everything that had happened to him.

Paul did not stay long in Nabatea. His seething energy could not bear inactivity. Soon after, he reappeared in Damascus and went to the synagogue on Sabbath. Of course, everyone was eager to heed the Sanhedrin’s envoy, who had disappeared shortly upon his arrival. What would he say? Would he refute the delusions of the new sect or demand immediate punishment for its members?

But instead, to everyone’s amazement, the Pharisee professed himself to be a follower of Jesus. He openly called Him the Son of God and the Anointed One.

Stunned, looking at each other in disbelief, they were asking among themselves: “Could it be the same Saul?” Yet out of respect for the guest from Jerusalem, they restrained themselves from interrupting his speech.

Day after day, the Tarsian preached, taught, and held disputes. The entire colony of Jews was at a loss not knowing what to do. However, as time passed, towards the end of the third year, the elders of the Damascus community finally lost their patience. They decided to dispose of Saul by their own means and “took counsel to kill him” (Acts 9:23).

At this time, the city was transferred by the Romans to the possession of the Nabatean king Aretas IV. An ethnarch (governor) began to rule in Damascus on behalf of the king.19 After he was informed that a certain Jew was sowing unrest, the ethnarch made orders to seize Paul and to guard all the city gates. The Tarsian escaped death by having been lowered in a large basket down the city wall during the night time.

He could have returned to his homeland Tarsus but first he felt compelled to come to grips with his past and visit Jerusalem where he had “persecuted Jesus” and His Church.

The return trip from Syria to Judea felt as a torture for Saul. After all, he had set out to Syria with a proud sense of fighting for a just cause only to return to Jerusalem laden with guilt, vividly remembering Stephen and knowing that the Nazarenes in Jerusalem dreaded a mere mention of Saul’s name.

Saul was returning alone. On the way back, he was wondering how his new coreligionists would receive him. Would not his conversion be viewed as an insidious move by a spy who sought to infiltrate their circle with the intention of destroying them? The very first meeting with the disciples showed that his fears were indeed justified. Paul was being shunned; they refused to talk to him, and not a single of them believed in his sincerity. Although few knew him personally, everyone could remember the role the merciless Pharisee played in the case of the Hellenists.

Feeling bitter, Paul was on the brink of departure. He understood why the believers were treating him that way; he would have likely acted similarly. Suddenly Joseph Barnabas, the patron of the Jerusalem Church, came to Paul’s aid. This humble and selfless Cypriot showed discernment and understanding toward Paul, having comprehended that Paul’s coming to the faith was a great gain for the brethren. After conversing with the Tarsian, he almost forcibly led him to Peter.

For the first time, the two future pillars of Christianity came face to face with each other—a fisherman from Capernaum and a learned rabbi, a native Israelite and a man raised in the Greek-speaking world. At first glance, they could not have been more different; yet Christ brought them together.

Paul also met James but did not seek to meet others of the Twelve. Still he spent two weeks with Peter in the house of Mary. All that time they talked and prayed together. The Pharisee was won over by Cephas’20 warmth. The apostle did not boast before the new convert, nor did he pride himself on knowing Jesus in the days of His ministry. It was the fact that the Messiah, no longer subject to death, was living again there and then among them rather than that of His earthly life that they both treasured the most.

Together with Peter, Paul visited the House of God, and there, during prayer, he was moved again by the sense of Christ’s presence. His voice resounded in the Pharisee’s heart, and now Paul’s calling was finally made clear: his word would not be received in Jerusalem; the Lord instead was sending him “far away to the Gentiles” (Acts 22:21).

Gentiles! The multifaceted world of nations who did not know God. They had long threatened Israel, and Israel had tried to fend them off and ignore them. Surrounded by them, the Old Testament Church saw itself as a type of ark, enveloped on all sides by the waves of the flood. Whenever an attempt at proselytizing was made, it focused on accepting a new individual on board of this ship and turning him into a Jew.

But now, by the will of Christ, the boundaries of the Church were expanding. Saul was called not just to “rescue” individual souls. A global task lay before him: to go into the thick of the pagan world and penetrate it with the light of the Gospel.

Arriving in his hometown, Paul apparently told his family about the transformation which had taken place in him, but he was not met with sympathy. In any case, we know nothing of his family there.21 Perhaps they stopped supporting him. Fortunately, Saul was able to provide for himself. According to custom, rabbis used to make a living by their handicraft while teaching the people for free. In his father’s workshop, Paul had learned how to make tents, which were willingly bought up by army suppliers and merchants.

Paul’s preaching in the synagogues of Tarsus was also unsuccessful: he shared the lot of many prophets who had been rejected in their own country. Yet the years he spent in his hometown would not go fruitless for the apostle. In fact, it was then that Paul, whom we know as the teacher of the faith, was formed.

What did the Gospel of Jesus Christ mean to him? First of all, a new stage, or phase, of the same Revelation, the beginning of which went back to the forefather Abraham. Whereas previously, the will of the Lord had been revealed only in the Law and in the teaching imparted by the prophets and sages, now God was speaking directly to people through His Anointed One.

The source of Paul’s spiritual power was living in Christ. Paul, who “had not known the Lord according to the flesh,”[20] was able to grasp and communicate the essence of the Gospel like no one before him. And this has become both a great lesson and hope for the Church.

Palestine – Syria, 36–43

The unexpected conversion of Paul, the resignation of Caiaphas, and the arrival of the procurator to Judea all helped bring the life of the Church back on a peaceful track. Furthermore, the domestic religious conflicts receded into the background as the entire country was faced with an external threat. In the spring of 37, the twenty-five-year-old Gaius Caligula was proclaimed emperor by the troops. He was beloved for his military courage, but it soon turned out that the new Caesar was a real monster, as the Romans themselves began to call him.[21–23] A mentally ill man, a maniac, and a sadist, he seriously fancied himself to be a god and demanded that altars and temples be built everywhere in his honor.

Although the Empire since the time of Augustus had already grown accustomed to it, the Jews, naturally, resisted the order and sent a deputation to Rome headed by Philo, hoping to get the order revoked. Caligula greeted the envoys with mockery and ordered the governor of Syria, Petronius, to erect his royal statue in the Temple of Jerusalem itself. If necessary, Petronius was allowed to resort to the use of violence. Judea was seething, and the people were ready to take up arms. Petronius was buying time because he realized that to carry out Caligula’s order meant to trigger a war. Agrippa I, the grandson of Herod the Great, who lived at the court of the emperor, urged him not to take such extreme measures. Finally, everyone breathed freely—on January 24, 41 AD, the conspirators did away with Gaius and elevated Claudius to the throne.

During this time, full of anxious expectations, many Nazarenes returned to Jerusalem and were able to live there free of persecution. However, the community’s life had changed; now, the practice of communal sharing of property had been replaced by organized care for the church’s poor.

At this time, the apostles received startling news: the Hellenist Philip, one of the Seven, began to baptize people of non-Jewish confession in Samaria.

Historians and biographers of Saul of Tarsus often portray him as the main initiator of the conversion of the Gentiles, who almost single-handedly “led the Church to the wide open spaces of the world.” In fact, Paul was not the first to embrace the idea of preaching the Gospel to the Gentiles. It started with the Hellenists who had left Jerusalem following the death of Stephen. Their mission would expand in concentric circles: from the Samaritans to the proselytes, and finally to the Gentiles. They were convinced that they must hurry to spread the news of Christ everywhere before His second coming.

Philip played a leading role among these preachers. Young and energetic, ready to proclaim Christ under any circumstances, he devoted himself entirely to the cause of evangelism.

When Peter and John Zebedee learned of the conversions among the Samaritans, they immediately set off for Samaria. The Jerusalem headquarters felt responsible for everything that went on in the Church. The journey of the apostles was not long: two or three days of travel and they arrived at their destination.

Having found Philip, the apostles became convinced that God had blessed his bold undertaking. He managed to achieve success quickly and break down the wall of alienation. Perhaps it helped that Philip was not a native Jerusalemite and spoke Greek. The Samaritans knew this language well: since the time of Pompey and Herod, their capital underwent a strong Hellenization and received the name of Sebastia.

“And there was great joy in that city,” remarks St. Luke (Acts 8:8). Philip taught, healed the sick, and baptized new converts. Among them was a certain Simon of Gitta, who was reputed to be a prophet and a conjurer. This strange character, highly popular among the Samaritans, was at first inseparable from Philip, which must have served to give more publicity to the Gospel’s preaching.

In history, the figure of Simon bifurcates, as it were, into two distinct characters. In Acts, he appears to be a simple-minded and superstitious person. On the other hand, his compatriot from Gitta, St. Justin (born c.100), portrays him as a theosophist—a mystic, the author of an intricate occult doctrine.22 The information about Simon, scattered among other antiquity writers, is extremely contradictory.[24–33] Some argue that he was an apologist of the Samaritan religion, others that he believed in a supreme deity, compared to whom the God of the Bible was an inferior and imperfect being.

Subsequently, the enchanter traveled far and wide, incorporating into his system various elements of the then fashionable teachings. In Alexandria, Simon became acquainted with aggressively anti-Jewish writings of Apion and adapted Apion’s views to his own. Thus, he allegedly claimed that “whoever believes the Old Testament is subject to death.”[31] If true, then Simon was encroaching on the Torah itself. However, back at the time of his meeting with Philip, he was still in the process of searching and was eager to join the new movement.

Simon, who was hungry for all kinds of miracles, was particularly struck by Philip’s healings. The apostle Peter, however, made on him an even greater impression. The Samaritan saw in the fisherman a powerful magician who possessed the main secrets of the “sect.” Upon his arrival in Samaria, Peter began to gather the newly-baptized for prayer. The apostle would lay his hands on people, and the Spirit of God overshadowed them—this was like a Samaritan Pentecost. People were mysteriously transformed, experiencing the Lord’s power.

Simon of Gitta was determined to acquire at all cost this power for himself, which he thought to be magical. He approached Peter with money, asking to be initiated into the mystery of administering of the Spirit. The apostle was deeply offended by this suggestion, which showed that the Samaritan viewed the grace of Christ as a magical gift that could be automatically sold or bought! “May your money perish with you,” Peter burst out, “because you thought that the gift of God could be purchased with money!” (Acts 8:20).

Simon, confused and frightened, began to ask for forgiveness. However, his remorse was hardly genuine. Once he realized that he would not be able to take the position in the church which he had hoped for, he left and founded his own sect. This sect would later be regarded as Christian even though it had nothing to do with the Gospel. According to tradition, Simon would continue to oppose the Apostle Peter for years everywhere Peter went, even as far as Rome.23

The Church Fathers saw Simon of Gitta as “the founder of all heresies.” Indeed, his theosophy, as far as we can tell, opened a long series of attempts to replace Christianity with a motley mixture of popular superstitions and Gnostic occultism. In those days, as during any time of crisis, people were especially keen on all kinds of arcane teachings allegedly containing “all the answers,” something that would allow the Simonians to continue to exist for the next several centuries.[34,35]

Meanwhile, Peter and John completed their mission among the newly baptized and returned to Jerusalem. On their way back, they themselves began to address the inhabitants of that area with the words of the Gospel. Their visit to Samaria also demonstrates just how fervently the Church was protecting her spiritual unity.24 From then on, the apostles and their successors would closely monitor everything that happened in their scattered communities, maintaining a genuine connection with them.

Twenty years after these events, the Evangelist Luke met Philip in Caesarea, from whom he learned about the further progress of preaching the Gospel in Palestine. In particular, Philip relayed to him an episode to which he attached great significance. Obeying a command from above, Philip abruptly left Samaria. God directed him to the road leading south from Jerusalem to Gaza. This may have seemed like a pointless exercise given that the city of Gaza with its surroundings had remained deserted since their destruction by Alexander’s troops. The evangelist Philip knew, however, that the Lord was calling him there for a reason.

And it came to pass that a lone chariot appeared on the abandoned old highway. It clearly belonged to a foreigner: chariots had not been used in Judea for a long time. Philip, without hesitation, caught up with the rider and began to walk alongside. A dark-skinned, fancifully dressed man sat in the carriage, reading aloud an open scroll. And, as happens during a long monotonous ride, the fellow travelers got into conversation. The visitor turned out to be a eunuch, courtier of the Ethiopian queen of Aksum. A Jewish colony had long existed in his homeland, and many Ethiopians favored the refined monotheism of the Bible. Among them was this nobleman, who was returning from his pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Having passed Gaza, he continued his way along the sea to far-off black Africa. This remarkable conversation between the representatives of such alien cultures was only made possible by two factors: the Jewish Diaspora and the spread of Hellenic civilization. Both travelers knew Greek and shared a common faith. The Ethiopian pilgrim was reading Isaiah in translation,25 and Philip inquired whether he understood what was written. The man replied that he would like to receive some clarification, and invited the Hellenist to join him in his chariot.

It is remarkable that Philip did not offer so much as a new doctrine or life rules to the stranger but, according to Luke, “preached the good news of Jesus” (Acts 8:35). His words were so convincing that his fellow traveler, seeing a pond near the road—probably dug by nomadic shepherds—posed a direct question: “Here is the water; what prevents me from being baptized?” (Acts 8:36).

Philip had always been quick and intuitive. He chose to disregard the fact that the entire instruction of the Ethiopian consisted of a single road conversation, and that, strictly speaking, he was not even a proselyte. Only those who had been made part of the Jewish community were considered true proselytes, whereas eunuchs could not be accepted into it.26 In a word, he was willing to overlook all the restrictions. The horses were stopped, and both the Hellenist and the African entered the water. Thus, the first representative of nations, to whom salvation had been promised through the ancient prophet, entered the family of Christ’s disciples.

There existed a tradition in the early Church that this man, baptized by Philip, later laid the foundation for Christianity in his homeland.27

Philip spent the subsequent years in the cities located off the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Israel, where he continued to preach. In Caesarea, he found himself a wife and settled permanently in this Hellenized city. He had four daughters who became famous for their prophetic gift. A new community of the faithful was formed around Philip destined to have a long and glorious history, which would become associated with the names of Origen, Pamphilus, and Eusebius.

As previously mentioned, a new tradition of visiting all recently formed churches was born during the events in Samaria. Therefore, around 40 AD, it became necessary to visit the Palestinian coastal region. The Apostle Peter, this time unaccompanied, set out on the journey again, “passing throughout all quarters” (Acts 9:32). His main goal was to attend to the organization of the young communities; and for them, the arrival of Peter was dear, above all, because they saw in the apostle a witness to the life and resurrection of the Messiah. The apostle continued his Teacher’s work: Luke speaks of two miracles performed by Peter in the coastal region, the rumor of which spread far and wide.

He stayed in Jaffa for a long time. The church there consisted mainly of poor folk, who had always been dear to the heart of the apostle. He chose to live with a tanner in a neighborhood considered “unclean” by the rabbis.

The Book of Acts emphasizes that the people in this “church of the poor” were especially cordial and helped each other whenever possible. The only wealthy member of the Jaffa fellowship was a certain Tabitha, and she too devoted all her strength to serving people. Together with pious widows, she sewed clothes for the poor.

To pagan Caesarea the Apostle Peter came under the most extraordinary circumstances. Orthodox Jews disliked that city, where the Procurator used to live, surrounded by offensive statues and imperial emblems. Perhaps, Peter, too, was reluctant to travel there, especially since there was no church in Caesarea at the time (Philip would settle in Caesarea at a later point). Yet God had a different plan.

One sweltering afternoon, the apostle went up to the roof of the tanner’s house for prayer at the appointed time. When he finished, the fisherman wanted to enter the upper room, where the women were preparing dinner for him. And at that moment, as if half-asleep, he saw a large piece of cloth tied at four corners let down in front of him. It contained animals prohibited for food by the Law. “And a voice came to him,” writes St. Luke, “Rise, Peter; kill and eat.” The apostle saw this as a test of his devoutness and resolutely refused. No “unclean food” would ever touch his mouth! Peter absorbed with his mother’s milk the age-old traditions that helped the Old Testament Church to stay separated from the Gentiles. These traditions had been sanctified by the blood of the martyrs. But the mysterious voice said: “What God has cleansed you must not call unclean.” The vision was repeated three times. Peter was perplexed. However, he soon became convinced that the vision had a deep meaning (Acts 10:9–18).28

The apostle had not yet come down from the roof when three strangers approached the house: a Roman soldier with two companions. They said they were sent by the Caesarean centurion29 Cornelius. Their master had long and sincerely believed in one God and was friends with the Jews. He belonged to the group of the so-called “God-fearing” or semi-proselytes, who, without performing all the rites of the Law, chose to substitute them with works of charity. And now God commanded him to meet with a certain Peter, who lived in Jaffa at a tanner’s place.

To invite pagans, even those who believed in God, into one’s house or visit them meant to go against the accepted practice. And Peter, probably, would have hesitated, had he not been under the impression of the strange vision. Did it not mean that it was the will of God for him to bypass the old order? He cordially received the Romans, allowed them to stay with him, and then followed them back to Caesarea the next morning. To emphasize the importance of the encounter, he took with him several Jewish brothers from Jaffa.

They walked along the sea coast quickly, without stopping. Finally, they could see the panorama of the city with its customs houses, theaters, and palaces. It was the first time the fisherman had seen that city, and everywhere he looked—there were signs of the Roman presence. Cornelius was already waiting for them, having gathered, as for a solemn occasion, his relatives and closest friends. He was the commander of a privileged Italian cohort, which included volunteers from Roman citizens of Italy (the bulk of the garrison consisted of Syrians, Greeks, and Samaritans); but, forgetting about the pride of an officer and a Roman, he greeted the Galilean fisherman at the door and bowed to the ground in an oriental manner. “Stand up; I am only a man myself,” the embarrassed Peter raised him and entered the house.

Upon seeing the audience, he immediately informed them that his coming had been precipitated by special circumstances. “You know,” he said, “that it is forbidden for a Jew to associate with or to visit anyone of another nation; but God has shown me that I should not call anyone impure or unclean” (Acts 10:24–28).

A conversation ensued, during which Cornelius recounted his recent vision. The apostle knew immediately that he was in the group of people marked by deep faith. He was astounded—the old notions were receding in the face of the new reality. “Truly I understand,” he admitted, “that God shows no partiality. But in every nation whoever fears Him and does what is right is accepted by Him. He has sent this Message to the people of Israel, preaching peace through Jesus Christ, who is Lord of all” (Acts 10:34–36).

Those present may have heard about the Man who had been executed by the procurator about ten years ago, and now they learned that “God raised Him up,” that He appeared to the chosen witnesses who ate and drank with the Risen One. “Of Him,” Peter concluded, “all the prophets testify that everyone believing in Him receives forgiveness of sins through His name” (Acts 10:43).

The Romans began to praise God and pray fervently. Their state was so familiar to Peter! Wasn’t that how the Spirit of God gave wings to the apostles on the day of Pentecost?

“Who can forbid those who, like us, have received the Holy Spirit to be baptized with water?” Peter exclaimed (Acts 10:47).

There had been a time when, in order to enter the Covenant, one had to “become a Jew.” Now God was opening new ways, for Jesus of Nazareth was “Lord of all.” The boundaries of God’s people were expanding, reaching the ends of the earth.